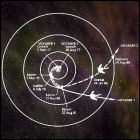

Recent Jet Propulsion Laboratory hire Michael Minovitch submits the first of a series of papers and technical memorandums on the possibility of using carefully-calculated gravitational assist maneuvers to speed transit time between celestial bodies while requiring minimal engine/fuel use. Where most previous scientific thought concentrated on using engine burns (and a lot of fuel) to cancel the effects of a planet’s gravity, Minovitch demonstrated that gravity could be a big help with a carefully calculated trajectory. Though nearly every planetary mission since then has capitalized on Minovitch’s research, it was initially rejected by JPL. Minovitch’s calculations are later revisited by Caltech grad student Gary Flandro, who flags down a particular combination of Minovitch’s pre-computed trajectories for a “grand tour” of the outer solar system, a mission which will eventually be known – in a somewhat scaled-down, less grand form – as Voyager.

Recent Jet Propulsion Laboratory hire Michael Minovitch submits the first of a series of papers and technical memorandums on the possibility of using carefully-calculated gravitational assist maneuvers to speed transit time between celestial bodies while requiring minimal engine/fuel use. Where most previous scientific thought concentrated on using engine burns (and a lot of fuel) to cancel the effects of a planet’s gravity, Minovitch demonstrated that gravity could be a big help with a carefully calculated trajectory. Though nearly every planetary mission since then has capitalized on Minovitch’s research, it was initially rejected by JPL. Minovitch’s calculations are later revisited by Caltech grad student Gary Flandro, who flags down a particular combination of Minovitch’s pre-computed trajectories for a “grand tour” of the outer solar system, a mission which will eventually be known – in a somewhat scaled-down, less grand form – as Voyager.

The Grand Tour Outer Planets mission is proposed to NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Using a combination of the gravitational assist trajectories computed by JPL’s Michael Minovitch in

The Grand Tour Outer Planets mission is proposed to NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Using a combination of the gravitational assist trajectories computed by JPL’s Michael Minovitch in  Astronomer James Christy, conducting observations of Pluto at the United States Naval Observatory, discovers a bulging shape present in some photos he’s taken of Pluto, but absent in others. Though the find meets with some skepticism, he has discovered the largest moon of Pluto, Charon, which has a mass of over 50% that of its parent body. Orbiting at only 11,000 miles from Pluto’s surface, Charon has a radius of 750 miles. Within 20 years, closer telescopic examination (including observations using the Hubble Space Telescope) confirm that Charon is separate from Pluto. Since the two bodies are relatively similar in mass, one doesn’t actually orbit the other; rather, they both orbit a center of mass – a barycenter – that lies close to, but not within, Pluto. Further observations in the 21st century lead to the unexpected discovery of four further satellites of Pluto.

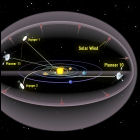

Astronomer James Christy, conducting observations of Pluto at the United States Naval Observatory, discovers a bulging shape present in some photos he’s taken of Pluto, but absent in others. Though the find meets with some skepticism, he has discovered the largest moon of Pluto, Charon, which has a mass of over 50% that of its parent body. Orbiting at only 11,000 miles from Pluto’s surface, Charon has a radius of 750 miles. Within 20 years, closer telescopic examination (including observations using the Hubble Space Telescope) confirm that Charon is separate from Pluto. Since the two bodies are relatively similar in mass, one doesn’t actually orbit the other; rather, they both orbit a center of mass – a barycenter – that lies close to, but not within, Pluto. Further observations in the 21st century lead to the unexpected discovery of four further satellites of Pluto. NASA’s Pioneer 10 unmanned spacecraft becomes the first human-made spacecraft to pass beyond the orbit of Pluto, the outermost known planet in the solar system. (Pioneer 10 merely crosses the planet’s orbital path; Pluto itself is in a different part of its orbit, nowhere near Pioneer at the time.) Launched in 1972, Pioneer 10 was the first spacecraft to cross the asteroid belt and observe the giant planet Jupiter at close range, blazing a trial for other outer solar system robotic exploration missions.

NASA’s Pioneer 10 unmanned spacecraft becomes the first human-made spacecraft to pass beyond the orbit of Pluto, the outermost known planet in the solar system. (Pioneer 10 merely crosses the planet’s orbital path; Pluto itself is in a different part of its orbit, nowhere near Pioneer at the time.) Launched in 1972, Pioneer 10 was the first spacecraft to cross the asteroid belt and observe the giant planet Jupiter at close range, blazing a trial for other outer solar system robotic exploration missions. Encouraged by the public interest in

Encouraged by the public interest in  NASA and JPL announce a plan is in the works to launch small twin spacecraft toward the planet Pluto. The Pluto Fast Flyby mission would launch two vehicles in 1997 or 1998, much smaller than the Voyager spacecraft that have explored the larger outer planets, with the two vehicles possibly arriving at Pluto as early as 2005 or 2007. Pluto Fast Flyby has the support of NASA’s new administrator and the White House, both of whom are insisting that NASA embrace a “faster, better, cheaper” space exploration philosophy. To save weight and energy, the initial mission proposal calls for no instruments other than cameras. This meets with protests from scientists (and proponents of the earlier

NASA and JPL announce a plan is in the works to launch small twin spacecraft toward the planet Pluto. The Pluto Fast Flyby mission would launch two vehicles in 1997 or 1998, much smaller than the Voyager spacecraft that have explored the larger outer planets, with the two vehicles possibly arriving at Pluto as early as 2005 or 2007. Pluto Fast Flyby has the support of NASA’s new administrator and the White House, both of whom are insisting that NASA embrace a “faster, better, cheaper” space exploration philosophy. To save weight and energy, the initial mission proposal calls for no instruments other than cameras. This meets with protests from scientists (and proponents of the earlier  After decades of the tiny object being seen only as a point of light in even the best telescopic images, the Hubble Space Telescope makes the first survey of the surface of Pluto. Even without the distortion introduced by Earth’s atmosphere, Hubble’s best shots of Pluto are vague due to the distance from Earth to Pluto, but they mark the first time that even blurry surface detail has been seen. The new images help NASA gain support for a Pluto flyby mission in the 21st century, which will eventually be named New Horizons.

After decades of the tiny object being seen only as a point of light in even the best telescopic images, the Hubble Space Telescope makes the first survey of the surface of Pluto. Even without the distortion introduced by Earth’s atmosphere, Hubble’s best shots of Pluto are vague due to the distance from Earth to Pluto, but they mark the first time that even blurry surface detail has been seen. The new images help NASA gain support for a Pluto flyby mission in the 21st century, which will eventually be named New Horizons. With NASA/JPL’s Pluto Fast Flyby mission cancelled, a new mission is proposed by several scientists and engineers, including veterans of the Voyager program, to send a small spacecraft to Pluto. Originally named Pluto Express, and later Pluto-Kuiper Express, the unmanned spacecraft would be armed with a handful of scientific instruments (as opposed to Pluto Fast Flyby’s camera-only proposal). Plans call for launch via a Delta Heavy rocket or from the cargo bay of a Space Shuttle in 2004, a Jupiter gravity assist flyby in 2006, and a Pluto flyby in 2012. Though there are early talks with the Russian space program about including landers or penetrators, that element of the mission is dropped soon afterward.

With NASA/JPL’s Pluto Fast Flyby mission cancelled, a new mission is proposed by several scientists and engineers, including veterans of the Voyager program, to send a small spacecraft to Pluto. Originally named Pluto Express, and later Pluto-Kuiper Express, the unmanned spacecraft would be armed with a handful of scientific instruments (as opposed to Pluto Fast Flyby’s camera-only proposal). Plans call for launch via a Delta Heavy rocket or from the cargo bay of a Space Shuttle in 2004, a Jupiter gravity assist flyby in 2006, and a Pluto flyby in 2012. Though there are early talks with the Russian space program about including landers or penetrators, that element of the mission is dropped soon afterward. In response to a NASA request for mission proposals a month earlier, Southwest Research Institute scientist Dr. Alan Stern and a group of other scientists and engineers who had been working on the now-cancelled Pluto-Kuiper Express mission submit a nearly-identical proposal to NASA for a Pluto/Kuiper Belt mission called New Horizons. Very much like Pluto-Kuiper Express, New Horizons calls for a single small spacecraft to launch early in the 21st century, and, after a gravity assist from a Jupiter flyby, a Pluto encounter 10-11 years after launch. Some of the program costs are streamlined in the new proposal to make this iteration of the long-delayed Pluto mission more appealing to NASA, although New Horizons would carry more scientific payload than any previously envisioned Pluto expedition. Another proposal, Pluto and Outer Solar System Explorer (POSSE), is also submitted to NASA.

In response to a NASA request for mission proposals a month earlier, Southwest Research Institute scientist Dr. Alan Stern and a group of other scientists and engineers who had been working on the now-cancelled Pluto-Kuiper Express mission submit a nearly-identical proposal to NASA for a Pluto/Kuiper Belt mission called New Horizons. Very much like Pluto-Kuiper Express, New Horizons calls for a single small spacecraft to launch early in the 21st century, and, after a gravity assist from a Jupiter flyby, a Pluto encounter 10-11 years after launch. Some of the program costs are streamlined in the new proposal to make this iteration of the long-delayed Pluto mission more appealing to NASA, although New Horizons would carry more scientific payload than any previously envisioned Pluto expedition. Another proposal, Pluto and Outer Solar System Explorer (POSSE), is also submitted to NASA. NASA launches the unmanned New Horizons probe on a course for the minor planet Pluto, the first spacecraft built to explore that destination. A trajectory with multiple planetary flybys and gravitational assists is designed to sling New Horizons toward Pluto within a decade (compared to Voyager 2’s 12-year trek to Neptune).

NASA launches the unmanned New Horizons probe on a course for the minor planet Pluto, the first spacecraft built to explore that destination. A trajectory with multiple planetary flybys and gravitational assists is designed to sling New Horizons toward Pluto within a decade (compared to Voyager 2’s 12-year trek to Neptune). Two tiny, recently-discovered satellites of dwarf planet Pluto have new named ratified by the International Astronomical Union; P4 is renamed Kerberos and P5 is renamed Styx. The names – related to the “underworld” theme that has governed the naming of Pluto and its moons to date – overlooks a popular online vote that suggested one of the moons should be named Vulcan, after Mr. Spock’s home planet in Star Trek. Kerberos, discoverd in 2011, is believed to be approximately 20 miles in diameter and orbits Pluto at a distance of roughly 37,000 miles. Styx, first sighted in 2012, is even smaller, with an estimated diameter of 15 miles, orbiting only 1,200 miles from Pluto, making it the innermost satellite (a distinction previously held by Pluto’s near-twin, Charon). NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft will have the opportunity to see the new moons up close when it does a flyby of Pluto in 2015.

Two tiny, recently-discovered satellites of dwarf planet Pluto have new named ratified by the International Astronomical Union; P4 is renamed Kerberos and P5 is renamed Styx. The names – related to the “underworld” theme that has governed the naming of Pluto and its moons to date – overlooks a popular online vote that suggested one of the moons should be named Vulcan, after Mr. Spock’s home planet in Star Trek. Kerberos, discoverd in 2011, is believed to be approximately 20 miles in diameter and orbits Pluto at a distance of roughly 37,000 miles. Styx, first sighted in 2012, is even smaller, with an estimated diameter of 15 miles, orbiting only 1,200 miles from Pluto, making it the innermost satellite (a distinction previously held by Pluto’s near-twin, Charon). NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft will have the opportunity to see the new moons up close when it does a flyby of Pluto in 2015. NASA’s New Horizons abruptly loses contact with Earth-based ground controllers and then signals that it has gone into safe mode, ten days before its closest flyby of Pluto. In this mode, the spacecraft gathers no scientific data, and awaits intervention from Earth, but its distance from Earth – four billion miles away – means that signals transmitted to or from New Horizons take four and a half hours to reach their destination (and any reply takes just as long). A timing error is located in New Horizons’ automatic event sequencer, a vital part of its mission since it will need to operate independently to conduct hundreds of observations of Pluto and its satellites with no contact from Earth until later, and the probe is rebooted within 48 hours. Though the probe’s automatic switch to failsafe mode has cost the mission some scientific observations, most of the high-value data will not be collected until within 24 hours of closest approach on July 14th.

NASA’s New Horizons abruptly loses contact with Earth-based ground controllers and then signals that it has gone into safe mode, ten days before its closest flyby of Pluto. In this mode, the spacecraft gathers no scientific data, and awaits intervention from Earth, but its distance from Earth – four billion miles away – means that signals transmitted to or from New Horizons take four and a half hours to reach their destination (and any reply takes just as long). A timing error is located in New Horizons’ automatic event sequencer, a vital part of its mission since it will need to operate independently to conduct hundreds of observations of Pluto and its satellites with no contact from Earth until later, and the probe is rebooted within 48 hours. Though the probe’s automatic switch to failsafe mode has cost the mission some scientific observations, most of the high-value data will not be collected until within 24 hours of closest approach on July 14th. Nine years after its launch from Earth, NASA’s New Horizons space probe passes within 8,000 miles of the surface of Pluto, and within 18,000 miles of Pluto’s largest moon, Charon. Detailed images and observations are obtained of both of these bodies, with less detailed data gathered on Pluto’s four smaller, outermost moons. Cruising through the Pluto system at 30,000 miles per hour, New Horizons must break contact with Earth for nearly a full day to aim its cameras and other instruments at their targets. It’s not until some 12 hours after the point of closest flyby that New Horizons re-establishes contact with Earth, reporting that it has successfully completed the encounter with no problems.

Nine years after its launch from Earth, NASA’s New Horizons space probe passes within 8,000 miles of the surface of Pluto, and within 18,000 miles of Pluto’s largest moon, Charon. Detailed images and observations are obtained of both of these bodies, with less detailed data gathered on Pluto’s four smaller, outermost moons. Cruising through the Pluto system at 30,000 miles per hour, New Horizons must break contact with Earth for nearly a full day to aim its cameras and other instruments at their targets. It’s not until some 12 hours after the point of closest flyby that New Horizons re-establishes contact with Earth, reporting that it has successfully completed the encounter with no problems. Picador publishes the non-fiction book

Picador publishes the non-fiction book