The Soviet Union attempts the first-ever launch of an interplanetary space probe bound for the planet Mars. A failure of its rocket booster prevents it from reaching enough thrust to leave Earth orbit; it eventually falls back to Earth and breaks up while reentering the atmosphere. As with many early Soviet space missions, it is not given any meaningful designation due to the failure of the mission.

The Soviet Union attempts the first-ever launch of an interplanetary space probe bound for the planet Mars. A failure of its rocket booster prevents it from reaching enough thrust to leave Earth orbit; it eventually falls back to Earth and breaks up while reentering the atmosphere. As with many early Soviet space missions, it is not given any meaningful designation due to the failure of the mission.

Though successfully launched, NASA’s

Though successfully launched, NASA’s  The Soviet Union launches the unmanned space probe Zond 2, intended to conduct the first close flyby of the planet Mars. Interplanetary exploration is still in its infancy, however, and just as Zond 1 failed mere weeks away from Venus, communication is lost with Zond 2 three months prior to its planned August 1965 encounter with the red planet. A backup of this spacecraft, Zond 3, will be launched in 1965, also failing to reach Mars but instead returning photos of Earth’s moon.

The Soviet Union launches the unmanned space probe Zond 2, intended to conduct the first close flyby of the planet Mars. Interplanetary exploration is still in its infancy, however, and just as Zond 1 failed mere weeks away from Venus, communication is lost with Zond 2 three months prior to its planned August 1965 encounter with the red planet. A backup of this spacecraft, Zond 3, will be launched in 1965, also failing to reach Mars but instead returning photos of Earth’s moon. Following up on preliminary studies assuming almost-Earthlike conditions, NASA commences work on a major robotic interplanetary landing mission called Voyager, which will use a Saturn IB rocket to send an orbiter with two landers to Mars. But NASA is doing so without much help from its usual interplanetary think-tank, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, whose scientists warn NASA that the latest astronomical data suggests a significantly thinner atmosphere and lower atmospheric pressure than the scenario for which NASA is designing its vehicles. As the complexity involved in creating self-guided landers with on-board laboratories increases, contractors begin to insist that only a Saturn V will do; since all Saturn V boosters are currently in reserve for Apollo lunar missions, NASA pushes the Voyager mission back into the 1970s.

Following up on preliminary studies assuming almost-Earthlike conditions, NASA commences work on a major robotic interplanetary landing mission called Voyager, which will use a Saturn IB rocket to send an orbiter with two landers to Mars. But NASA is doing so without much help from its usual interplanetary think-tank, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, whose scientists warn NASA that the latest astronomical data suggests a significantly thinner atmosphere and lower atmospheric pressure than the scenario for which NASA is designing its vehicles. As the complexity involved in creating self-guided landers with on-board laboratories increases, contractors begin to insist that only a Saturn V will do; since all Saturn V boosters are currently in reserve for Apollo lunar missions, NASA pushes the Voyager mission back into the 1970s. Mariner 4 successfully passes by Mars at a distance of just over 6,000 miles, and transmits the first direct measurements of the Martian environment to Earth, along with the first pictures ever taken of another planet from a nearby spacecraft. Mariner 4’s onboard instruments detect a thin atmosphere – thin enough that any future landing attempts will need to descend on retro rockets, but thick enough that a heat shield is still necessary. These findings have a ripple effect on

Mariner 4 successfully passes by Mars at a distance of just over 6,000 miles, and transmits the first direct measurements of the Martian environment to Earth, along with the first pictures ever taken of another planet from a nearby spacecraft. Mariner 4’s onboard instruments detect a thin atmosphere – thin enough that any future landing attempts will need to descend on retro rockets, but thick enough that a heat shield is still necessary. These findings have a ripple effect on  NASA and JPL launch the unmanned Mariner 6 space probe on a mission to Mars, where it will be joined by its yet-to-be-launched identical twin, Mariner 7. Mariner 6 will take five months to reach the red planet, with its slightly faster sister ship mere days behind it, and will fly past Mars twice as close as the planet’s previous unmanned visitors.

NASA and JPL launch the unmanned Mariner 6 space probe on a mission to Mars, where it will be joined by its yet-to-be-launched identical twin, Mariner 7. Mariner 6 will take five months to reach the red planet, with its slightly faster sister ship mere days behind it, and will fly past Mars twice as close as the planet’s previous unmanned visitors. The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Mariner 6 makes its closest flyby of planet Mars, coming as close as just over 2100 miles from the Martian surface. While measuring the composition of the Martian atmosphere and trying to analyze its surface from space, Mariner 6 passes over densely cratered terrain, not spotting the huge canyons and volcanoes that will later become synonymous with Mars. Mariner 6’s identical twin, Mariner 7, is just days behind it, and ground controllers rewrite Mariner 7’s flight plan to get closer looks at surface features first spotted by Mariner 6.

The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Mariner 6 makes its closest flyby of planet Mars, coming as close as just over 2100 miles from the Martian surface. While measuring the composition of the Martian atmosphere and trying to analyze its surface from space, Mariner 6 passes over densely cratered terrain, not spotting the huge canyons and volcanoes that will later become synonymous with Mars. Mariner 6’s identical twin, Mariner 7, is just days behind it, and ground controllers rewrite Mariner 7’s flight plan to get closer looks at surface features first spotted by Mariner 6. The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Mariner 7 makes its closest flyby of planet Mars, coming as close as just over 2100 miles from the Martian surface. Having recently suffered an inexplicable but temporary loss of communications with Earth (later determined to be caused by a leaky on-board battery), Mariner 7’s flight plan is reprogrammed just days out from Mars based on some of the more interesting findings of its sister ship, Mariner 6. The success of the tandem flight to Mars convinces NASA to adopt a similar mission profile for the upcoming Mars ’71 missions, which will send two Mariner orbiters to take up permanent positions around Mars.

The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Mariner 7 makes its closest flyby of planet Mars, coming as close as just over 2100 miles from the Martian surface. Having recently suffered an inexplicable but temporary loss of communications with Earth (later determined to be caused by a leaky on-board battery), Mariner 7’s flight plan is reprogrammed just days out from Mars based on some of the more interesting findings of its sister ship, Mariner 6. The success of the tandem flight to Mars convinces NASA to adopt a similar mission profile for the upcoming Mars ’71 missions, which will send two Mariner orbiters to take up permanent positions around Mars. NASA begins making detailed plans for a pair of orbiter/lander spacecraft, now named Viking, to be sent to Mars in the mid 1970s (possibly as early as

NASA begins making detailed plans for a pair of orbiter/lander spacecraft, now named Viking, to be sent to Mars in the mid 1970s (possibly as early as  NASA and JPL launch Mariner 8, the first of two identical “Mars ’71” orbiters designed to visit Mars. Where previous missions have simply flown past the red planet, Mariners 8 and 9 are intended to put themselves in orbit and remain there to map the majority of the Martian surface. The second stage of the Atlas-Centaur booster used to launch Mariner 8 fails, however, and the robotic Mars explorer crashes into the Atlantic Ocean. Some of its mission objectives are transferred to the identical Mariner 9, due for launch at the end of the month.

NASA and JPL launch Mariner 8, the first of two identical “Mars ’71” orbiters designed to visit Mars. Where previous missions have simply flown past the red planet, Mariners 8 and 9 are intended to put themselves in orbit and remain there to map the majority of the Martian surface. The second stage of the Atlas-Centaur booster used to launch Mariner 8 fails, however, and the robotic Mars explorer crashes into the Atlantic Ocean. Some of its mission objectives are transferred to the identical Mariner 9, due for launch at the end of the month. The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Mariner 9 enters orbit around Mars, becoming the first human spacecraft to orbit another planet in the solar system. The probe begins a nearly year-long survey of the red planet, mapping over 70% of its surface at a much higher resolution than was achieved by the previous NASA Mars probes, Mariners 6 and 7. Mariner 9’s mapping mission is temporarily delayed by a global dust storm obscuring the entire planet when the orbiter arrives. Among its discoveries are Olympus Mons, the solar system’s largest volcano, and the gigantic canyon later named Valles Marineris. Mariner 9 also gathers images of Mars’ two moons, Phobos and Deimos.

The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Mariner 9 enters orbit around Mars, becoming the first human spacecraft to orbit another planet in the solar system. The probe begins a nearly year-long survey of the red planet, mapping over 70% of its surface at a much higher resolution than was achieved by the previous NASA Mars probes, Mariners 6 and 7. Mariner 9’s mapping mission is temporarily delayed by a global dust storm obscuring the entire planet when the orbiter arrives. Among its discoveries are Olympus Mons, the solar system’s largest volcano, and the gigantic canyon later named Valles Marineris. Mariner 9 also gathers images of Mars’ two moons, Phobos and Deimos. NASA’s Mariner 9 Mars orbiter becomes the first spacecraft to provide relatively close-up images of Mars’ innermost, larger moon, Phobos, from over 3,500 miles away. The irregular shape and heavily cratered surface of Phobos point up its likely origins as an asteroid that long ago came close enough to Mars to be captured into an orbit. Phobos (and its still unseen-at-close-range smaller sibling, Deimos) will be imaged at much closer range later in the 1970s by the Viking orbiters.

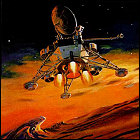

NASA’s Mariner 9 Mars orbiter becomes the first spacecraft to provide relatively close-up images of Mars’ innermost, larger moon, Phobos, from over 3,500 miles away. The irregular shape and heavily cratered surface of Phobos point up its likely origins as an asteroid that long ago came close enough to Mars to be captured into an orbit. Phobos (and its still unseen-at-close-range smaller sibling, Deimos) will be imaged at much closer range later in the 1970s by the Viking orbiters. The Viking 1 unmanned space probe, built by NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, lifts off en route to the planet Mars. Intended to gather and study soil samples on-site on the Martian surface, Viking 1 will take eleven months to reach the red planet. Viking 1 is not the first attempt to land a spacecraft on Mars; the Soviet Union has been attempting such a feat since the 1960s.

The Viking 1 unmanned space probe, built by NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, lifts off en route to the planet Mars. Intended to gather and study soil samples on-site on the Martian surface, Viking 1 will take eleven months to reach the red planet. Viking 1 is not the first attempt to land a spacecraft on Mars; the Soviet Union has been attempting such a feat since the 1960s. NASA launches the Viking 2 lander and orbiter, designed and operated by Jet Propulsion Laboratory, aboard a Titan IIIE rocket bound for Mars. The combined Viking 2 spacecraft will take nearly a year to reach Mars, achieving orbit in August 1976 and surveying the surface for suitable landing sites before the northern plain named Utopia Planitia is selected for a September 1976 landing attempt.

NASA launches the Viking 2 lander and orbiter, designed and operated by Jet Propulsion Laboratory, aboard a Titan IIIE rocket bound for Mars. The combined Viking 2 spacecraft will take nearly a year to reach Mars, achieving orbit in August 1976 and surveying the surface for suitable landing sites before the northern plain named Utopia Planitia is selected for a September 1976 landing attempt. Viking 1 makes a soft landing on Mars, the first spacecraft to do so intact (the Soviet space program had been attempting to put landers on Mars, some of them including rudimentary rovers, since 1962). It successfully transmits the first picture from the Martian surface back to Earth within seconds, and successfully gathers soil samples for analysis. Viking 1’s orbiter mothership will later shut down in 1980, but the lander itself functions until 1982. Viking 1’s landing takes place on the seventh anniversary of the first manned moon landing.

Viking 1 makes a soft landing on Mars, the first spacecraft to do so intact (the Soviet space program had been attempting to put landers on Mars, some of them including rudimentary rovers, since 1962). It successfully transmits the first picture from the Martian surface back to Earth within seconds, and successfully gathers soil samples for analysis. Viking 1’s orbiter mothership will later shut down in 1980, but the lander itself functions until 1982. Viking 1’s landing takes place on the seventh anniversary of the first manned moon landing. The Viking 1 orbiter, observing Mars from orbit while relaying data from the Viking 1 lander to Earth, snaps a close-up view of the Martian moon Phobos from within 5,000 miles. Though more distant from Phobos than Mariner 9’s closest pass in 1972, the Viking cameras are vastly superior, revealing greater detail even at greater distances; craters as small as 13 miles across can be seen in the images. JPL scientists and mission planners are already developing ideas for future Mars missions, including unmanned landers with wheeled rovers.

The Viking 1 orbiter, observing Mars from orbit while relaying data from the Viking 1 lander to Earth, snaps a close-up view of the Martian moon Phobos from within 5,000 miles. Though more distant from Phobos than Mariner 9’s closest pass in 1972, the Viking cameras are vastly superior, revealing greater detail even at greater distances; craters as small as 13 miles across can be seen in the images. JPL scientists and mission planners are already developing ideas for future Mars missions, including unmanned landers with wheeled rovers. NASA’s Viking 2 lander, launched from Earth almost exactly a year earlier touches down on Martian soil in the Utopia Planitia region. One of Viking 2’s three landing legs comes down on a rock, leaving the entire lander at an eight-degree angle to the ground. Identical to Viking 1, Viking 2 has its own soil sampling arm, though its series of tests for biological reactions within the soil produce inconclusive results (including at least one “positive” test for signs of life, later attributed to inorganic chemical reactions). Viking 2 will also later confirm that water exists, at least briefly, on the surface of Mars in the form of frost.

NASA’s Viking 2 lander, launched from Earth almost exactly a year earlier touches down on Martian soil in the Utopia Planitia region. One of Viking 2’s three landing legs comes down on a rock, leaving the entire lander at an eight-degree angle to the ground. Identical to Viking 1, Viking 2 has its own soil sampling arm, though its series of tests for biological reactions within the soil produce inconclusive results (including at least one “positive” test for signs of life, later attributed to inorganic chemical reactions). Viking 2 will also later confirm that water exists, at least briefly, on the surface of Mars in the form of frost. NASA’s Viking 2 lander confirms a surprising finding first detected in black-and-white images just days earlier: Mars has naturally occurring frost. Scientists try to determine, from images alone, if the frost forms from condensation due to overnight cold (as on Earth), or through some other atmospheric mechanism. But the finding does confirm enough moisture in the atmosphere to condense on the Martian surface, decades before surface water is confirmed on the red planet.

NASA’s Viking 2 lander confirms a surprising finding first detected in black-and-white images just days earlier: Mars has naturally occurring frost. Scientists try to determine, from images alone, if the frost forms from condensation due to overnight cold (as on Earth), or through some other atmospheric mechanism. But the finding does confirm enough moisture in the atmosphere to condense on the Martian surface, decades before surface water is confirmed on the red planet. NASA’s Viking 2 orbiter closes to within 40 miles of Mars’ small outermost moon, Deimos, the first spacecraft to visit the tiny moon up close. Deimos is found to be cratered and irregularly shaped, confirming the likelihood that it is an asteroid that once strayed close enough to Mars to fall into orbit.

NASA’s Viking 2 orbiter closes to within 40 miles of Mars’ small outermost moon, Deimos, the first spacecraft to visit the tiny moon up close. Deimos is found to be cratered and irregularly shaped, confirming the likelihood that it is an asteroid that once strayed close enough to Mars to fall into orbit. Less than two years after arriving at Mars, the “mothership” orbiter that delivered the

Less than two years after arriving at Mars, the “mothership” orbiter that delivered the  Two years after the shutdown of its orbiter leaves it sending observations of the Martian environment back to Earth at a low bit rate, the

Two years after the shutdown of its orbiter leaves it sending observations of the Martian environment back to Earth at a low bit rate, the  After over six years of continuous operation and data gathering on the planet Mars, the Viking 1 lander – having outlived the power supply aboard its orbiter and now transmitting its observations directly to Earth – is inadvertently silenced during what is intended to be a remote upgrade of its on-board software. Ground controllers are never able to establish contact with Viking 1 again. Its record of continuous operation on another planet is not broken until 2010, when Viking 1 is outlasted by NASA’s Opportunity rover.

After over six years of continuous operation and data gathering on the planet Mars, the Viking 1 lander – having outlived the power supply aboard its orbiter and now transmitting its observations directly to Earth – is inadvertently silenced during what is intended to be a remote upgrade of its on-board software. Ground controllers are never able to establish contact with Viking 1 again. Its record of continuous operation on another planet is not broken until 2010, when Viking 1 is outlasted by NASA’s Opportunity rover. The Soviet Union launches the first of two unmanned Phobos space probes, designed to investigate the largest of Mars’ two asteroid-like moons and deliver a lander to analyze that moon’s surface. With multiple nations pitching in resources to help the mission succeed, including the United States, the Phobos program is intended to be the definitive Mars exploration program of the 1980s, as well as the debut of a new Soviet interplanetary vehicle to take over from the Zond/Venera design in use since the 1960s.

The Soviet Union launches the first of two unmanned Phobos space probes, designed to investigate the largest of Mars’ two asteroid-like moons and deliver a lander to analyze that moon’s surface. With multiple nations pitching in resources to help the mission succeed, including the United States, the Phobos program is intended to be the definitive Mars exploration program of the 1980s, as well as the debut of a new Soviet interplanetary vehicle to take over from the Zond/Venera design in use since the 1960s.