After data returned by JPL’s Mariner spacecraft reveals that – as JPL predicted – Mars has a thin atmosphere and very low atmospheric pressure, plans for a Saturn V-launched orbiter with two 10,000-pound Mars landers are scuttled. The Voyager Mars mission, not expected to launch until 1973, proved too complex and costly for the current state of the art. The Voyager name will later be bestowed upon a pair of Mariner spacecraft exploring beyond the orbit of Mars, while the Voyager concept will later be scaled down to a more feasible and cost-effective orbiter/lander combination called Viking.

After data returned by JPL’s Mariner spacecraft reveals that – as JPL predicted – Mars has a thin atmosphere and very low atmospheric pressure, plans for a Saturn V-launched orbiter with two 10,000-pound Mars landers are scuttled. The Voyager Mars mission, not expected to launch until 1973, proved too complex and costly for the current state of the art. The Voyager name will later be bestowed upon a pair of Mariner spacecraft exploring beyond the orbit of Mars, while the Voyager concept will later be scaled down to a more feasible and cost-effective orbiter/lander combination called Viking.

NASA begins making detailed plans for a pair of orbiter/lander spacecraft, now named Viking, to be sent to Mars in the mid 1970s (possibly as early as

NASA begins making detailed plans for a pair of orbiter/lander spacecraft, now named Viking, to be sent to Mars in the mid 1970s (possibly as early as  In advance of the Viking and Voyager interplanetary missions, which will need more powerful boosters to heft heavier spacecraft into deep space, NASA conducts a test launch of the Titan IIIe/Centaur launch stack, an experimental combination of the venerable Titan rocket and a liquid-fueled Centaur upper stage. Previous Centaur upper stages were attached to wider Atlas rockets, so the unusual bulb-shaped payload shroud of the Centaur is of concern when placed atop the Titan, which has a more narrow diameter; if successful, however, this configuration could launch payloads three times larger than an Atlas/Centaur combination. The test flight, originally scheduled for January 24th, actually fails – a loose part causes the Centaur stage to fizzle rather than fire – and the rocket is destroyed in mid-air. However, with worries about the large Centaur payload atop the narrow Titan rocket laid to rest, NASA approves the Titan IIIe/Centaur for flight, beginning with the launch of a joint American/German science satellite, HELIOS-1, later in 1974.

In advance of the Viking and Voyager interplanetary missions, which will need more powerful boosters to heft heavier spacecraft into deep space, NASA conducts a test launch of the Titan IIIe/Centaur launch stack, an experimental combination of the venerable Titan rocket and a liquid-fueled Centaur upper stage. Previous Centaur upper stages were attached to wider Atlas rockets, so the unusual bulb-shaped payload shroud of the Centaur is of concern when placed atop the Titan, which has a more narrow diameter; if successful, however, this configuration could launch payloads three times larger than an Atlas/Centaur combination. The test flight, originally scheduled for January 24th, actually fails – a loose part causes the Centaur stage to fizzle rather than fire – and the rocket is destroyed in mid-air. However, with worries about the large Centaur payload atop the narrow Titan rocket laid to rest, NASA approves the Titan IIIe/Centaur for flight, beginning with the launch of a joint American/German science satellite, HELIOS-1, later in 1974. The Viking 1 unmanned space probe, built by NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, lifts off en route to the planet Mars. Intended to gather and study soil samples on-site on the Martian surface, Viking 1 will take eleven months to reach the red planet. Viking 1 is not the first attempt to land a spacecraft on Mars; the Soviet Union has been attempting such a feat since the 1960s.

The Viking 1 unmanned space probe, built by NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, lifts off en route to the planet Mars. Intended to gather and study soil samples on-site on the Martian surface, Viking 1 will take eleven months to reach the red planet. Viking 1 is not the first attempt to land a spacecraft on Mars; the Soviet Union has been attempting such a feat since the 1960s. NASA launches the Viking 2 lander and orbiter, designed and operated by Jet Propulsion Laboratory, aboard a Titan IIIE rocket bound for Mars. The combined Viking 2 spacecraft will take nearly a year to reach Mars, achieving orbit in August 1976 and surveying the surface for suitable landing sites before the northern plain named Utopia Planitia is selected for a September 1976 landing attempt.

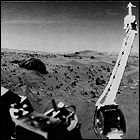

NASA launches the Viking 2 lander and orbiter, designed and operated by Jet Propulsion Laboratory, aboard a Titan IIIE rocket bound for Mars. The combined Viking 2 spacecraft will take nearly a year to reach Mars, achieving orbit in August 1976 and surveying the surface for suitable landing sites before the northern plain named Utopia Planitia is selected for a September 1976 landing attempt. Viking 1 makes a soft landing on Mars, the first spacecraft to do so intact (the Soviet space program had been attempting to put landers on Mars, some of them including rudimentary rovers, since 1962). It successfully transmits the first picture from the Martian surface back to Earth within seconds, and successfully gathers soil samples for analysis. Viking 1’s orbiter mothership will later shut down in 1980, but the lander itself functions until 1982. Viking 1’s landing takes place on the seventh anniversary of the first manned moon landing.

Viking 1 makes a soft landing on Mars, the first spacecraft to do so intact (the Soviet space program had been attempting to put landers on Mars, some of them including rudimentary rovers, since 1962). It successfully transmits the first picture from the Martian surface back to Earth within seconds, and successfully gathers soil samples for analysis. Viking 1’s orbiter mothership will later shut down in 1980, but the lander itself functions until 1982. Viking 1’s landing takes place on the seventh anniversary of the first manned moon landing. The Viking 1 orbiter, observing Mars from orbit while relaying data from the Viking 1 lander to Earth, snaps a close-up view of the Martian moon Phobos from within 5,000 miles. Though more distant from Phobos than Mariner 9’s closest pass in 1972, the Viking cameras are vastly superior, revealing greater detail even at greater distances; craters as small as 13 miles across can be seen in the images. JPL scientists and mission planners are already developing ideas for future Mars missions, including unmanned landers with wheeled rovers.

The Viking 1 orbiter, observing Mars from orbit while relaying data from the Viking 1 lander to Earth, snaps a close-up view of the Martian moon Phobos from within 5,000 miles. Though more distant from Phobos than Mariner 9’s closest pass in 1972, the Viking cameras are vastly superior, revealing greater detail even at greater distances; craters as small as 13 miles across can be seen in the images. JPL scientists and mission planners are already developing ideas for future Mars missions, including unmanned landers with wheeled rovers. NASA’s Viking 2 lander, launched from Earth almost exactly a year earlier touches down on Martian soil in the Utopia Planitia region. One of Viking 2’s three landing legs comes down on a rock, leaving the entire lander at an eight-degree angle to the ground. Identical to Viking 1, Viking 2 has its own soil sampling arm, though its series of tests for biological reactions within the soil produce inconclusive results (including at least one “positive” test for signs of life, later attributed to inorganic chemical reactions). Viking 2 will also later confirm that water exists, at least briefly, on the surface of Mars in the form of frost.

NASA’s Viking 2 lander, launched from Earth almost exactly a year earlier touches down on Martian soil in the Utopia Planitia region. One of Viking 2’s three landing legs comes down on a rock, leaving the entire lander at an eight-degree angle to the ground. Identical to Viking 1, Viking 2 has its own soil sampling arm, though its series of tests for biological reactions within the soil produce inconclusive results (including at least one “positive” test for signs of life, later attributed to inorganic chemical reactions). Viking 2 will also later confirm that water exists, at least briefly, on the surface of Mars in the form of frost. NASA’s Viking 2 lander confirms a surprising finding first detected in black-and-white images just days earlier: Mars has naturally occurring frost. Scientists try to determine, from images alone, if the frost forms from condensation due to overnight cold (as on Earth), or through some other atmospheric mechanism. But the finding does confirm enough moisture in the atmosphere to condense on the Martian surface, decades before surface water is confirmed on the red planet.

NASA’s Viking 2 lander confirms a surprising finding first detected in black-and-white images just days earlier: Mars has naturally occurring frost. Scientists try to determine, from images alone, if the frost forms from condensation due to overnight cold (as on Earth), or through some other atmospheric mechanism. But the finding does confirm enough moisture in the atmosphere to condense on the Martian surface, decades before surface water is confirmed on the red planet. NASA’s Viking 2 orbiter closes to within 40 miles of Mars’ small outermost moon, Deimos, the first spacecraft to visit the tiny moon up close. Deimos is found to be cratered and irregularly shaped, confirming the likelihood that it is an asteroid that once strayed close enough to Mars to fall into orbit.

NASA’s Viking 2 orbiter closes to within 40 miles of Mars’ small outermost moon, Deimos, the first spacecraft to visit the tiny moon up close. Deimos is found to be cratered and irregularly shaped, confirming the likelihood that it is an asteroid that once strayed close enough to Mars to fall into orbit. Less than two years after arriving at Mars, the “mothership” orbiter that delivered the

Less than two years after arriving at Mars, the “mothership” orbiter that delivered the  Two years after the shutdown of its orbiter leaves it sending observations of the Martian environment back to Earth at a low bit rate, the

Two years after the shutdown of its orbiter leaves it sending observations of the Martian environment back to Earth at a low bit rate, the  After over six years of continuous operation and data gathering on the planet Mars, the Viking 1 lander – having outlived the power supply aboard its orbiter and now transmitting its observations directly to Earth – is inadvertently silenced during what is intended to be a remote upgrade of its on-board software. Ground controllers are never able to establish contact with Viking 1 again. Its record of continuous operation on another planet is not broken until 2010, when Viking 1 is outlasted by NASA’s Opportunity rover.

After over six years of continuous operation and data gathering on the planet Mars, the Viking 1 lander – having outlived the power supply aboard its orbiter and now transmitting its observations directly to Earth – is inadvertently silenced during what is intended to be a remote upgrade of its on-board software. Ground controllers are never able to establish contact with Viking 1 again. Its record of continuous operation on another planet is not broken until 2010, when Viking 1 is outlasted by NASA’s Opportunity rover. Bradford A. Smith, a research astronomer and former professor of planetary science and astronomy at the University of Arizona, dies at the age of 86 from complications arising from an autoimmune disorder. Smith became a public figure during the peak years of the uncrewed

Bradford A. Smith, a research astronomer and former professor of planetary science and astronomy at the University of Arizona, dies at the age of 86 from complications arising from an autoimmune disorder. Smith became a public figure during the peak years of the uncrewed