NASA launches the JPL-built unmanned space probe Mariner 1, the first of two identical spacecraft intended to study the planet Venus. Mariner 1’s mission, however, is cut short before it even leaves Earth’s atmosphere: a communication loss between its Atlas-Agena booster rocket and ground-based control systems sends the rocket off course. Fearing that it might tumble into the Atlantic Ocean’s heavily traveled shipping lanes, NASA orders the vehicle to self-destruct in mid-air. Many later accounts lay the blame at an error in the code loaded into the rocket’s on-board guidance computer. Mariner 1’s mission objectives are transferred to its identical twin, Mariner 2, due to be launched in just over a month.

NASA launches the JPL-built unmanned space probe Mariner 1, the first of two identical spacecraft intended to study the planet Venus. Mariner 1’s mission, however, is cut short before it even leaves Earth’s atmosphere: a communication loss between its Atlas-Agena booster rocket and ground-based control systems sends the rocket off course. Fearing that it might tumble into the Atlantic Ocean’s heavily traveled shipping lanes, NASA orders the vehicle to self-destruct in mid-air. Many later accounts lay the blame at an error in the code loaded into the rocket’s on-board guidance computer. Mariner 1’s mission objectives are transferred to its identical twin, Mariner 2, due to be launched in just over a month.

NASA launches its first interplanetary spacecraft, the unmanned space probe Mariner 2, en route to Venus. During its three-month trip from Earth to Venus, Mariner 2 takes measurements of solar wind, charged particles, and an experiment is included to measure the amount of dust and micrometeoroids between the two planets. The probe briefly loses attitude control several times in flight, but regains proper orientation in each instance.

NASA launches its first interplanetary spacecraft, the unmanned space probe Mariner 2, en route to Venus. During its three-month trip from Earth to Venus, Mariner 2 takes measurements of solar wind, charged particles, and an experiment is included to measure the amount of dust and micrometeoroids between the two planets. The probe briefly loses attitude control several times in flight, but regains proper orientation in each instance. NASA’s unmanned Mariner 2 probe is the first unmanned spacecraft to successfully reach and take measuresments of another planet in the solar system. Passing by Venus at a distance of 25,000 miles, Mariner 2 detects a cool atmosphere with a blistering hot surface underneath it – quickly dispelling any hopes of finding life there. Mariner 2 isn’t equipped with any cameras, which is just as well: unless any cameras had ultraviolet filters, they would have seen nothing but featureless clouds at Venus. Mariner 2 continues on into a solar orbit, shutting down early in 1963.

NASA’s unmanned Mariner 2 probe is the first unmanned spacecraft to successfully reach and take measuresments of another planet in the solar system. Passing by Venus at a distance of 25,000 miles, Mariner 2 detects a cool atmosphere with a blistering hot surface underneath it – quickly dispelling any hopes of finding life there. Mariner 2 isn’t equipped with any cameras, which is just as well: unless any cameras had ultraviolet filters, they would have seen nothing but featureless clouds at Venus. Mariner 2 continues on into a solar orbit, shutting down early in 1963. Though successfully launched, NASA’s

Though successfully launched, NASA’s  Mariner 4 successfully passes by Mars at a distance of just over 6,000 miles, and transmits the first direct measurements of the Martian environment to Earth, along with the first pictures ever taken of another planet from a nearby spacecraft. Mariner 4’s onboard instruments detect a thin atmosphere – thin enough that any future landing attempts will need to descend on retro rockets, but thick enough that a heat shield is still necessary. These findings have a ripple effect on

Mariner 4 successfully passes by Mars at a distance of just over 6,000 miles, and transmits the first direct measurements of the Martian environment to Earth, along with the first pictures ever taken of another planet from a nearby spacecraft. Mariner 4’s onboard instruments detect a thin atmosphere – thin enough that any future landing attempts will need to descend on retro rockets, but thick enough that a heat shield is still necessary. These findings have a ripple effect on  NASA and JPL launch the unmanned Mariner 6 space probe on a mission to Mars, where it will be joined by its yet-to-be-launched identical twin, Mariner 7. Mariner 6 will take five months to reach the red planet, with its slightly faster sister ship mere days behind it, and will fly past Mars twice as close as the planet’s previous unmanned visitors.

NASA and JPL launch the unmanned Mariner 6 space probe on a mission to Mars, where it will be joined by its yet-to-be-launched identical twin, Mariner 7. Mariner 6 will take five months to reach the red planet, with its slightly faster sister ship mere days behind it, and will fly past Mars twice as close as the planet’s previous unmanned visitors. The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Mariner 6 makes its closest flyby of planet Mars, coming as close as just over 2100 miles from the Martian surface. While measuring the composition of the Martian atmosphere and trying to analyze its surface from space, Mariner 6 passes over densely cratered terrain, not spotting the huge canyons and volcanoes that will later become synonymous with Mars. Mariner 6’s identical twin, Mariner 7, is just days behind it, and ground controllers rewrite Mariner 7’s flight plan to get closer looks at surface features first spotted by Mariner 6.

The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Mariner 6 makes its closest flyby of planet Mars, coming as close as just over 2100 miles from the Martian surface. While measuring the composition of the Martian atmosphere and trying to analyze its surface from space, Mariner 6 passes over densely cratered terrain, not spotting the huge canyons and volcanoes that will later become synonymous with Mars. Mariner 6’s identical twin, Mariner 7, is just days behind it, and ground controllers rewrite Mariner 7’s flight plan to get closer looks at surface features first spotted by Mariner 6. The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Mariner 7 makes its closest flyby of planet Mars, coming as close as just over 2100 miles from the Martian surface. Having recently suffered an inexplicable but temporary loss of communications with Earth (later determined to be caused by a leaky on-board battery), Mariner 7’s flight plan is reprogrammed just days out from Mars based on some of the more interesting findings of its sister ship, Mariner 6. The success of the tandem flight to Mars convinces NASA to adopt a similar mission profile for the upcoming Mars ’71 missions, which will send two Mariner orbiters to take up permanent positions around Mars.

The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Mariner 7 makes its closest flyby of planet Mars, coming as close as just over 2100 miles from the Martian surface. Having recently suffered an inexplicable but temporary loss of communications with Earth (later determined to be caused by a leaky on-board battery), Mariner 7’s flight plan is reprogrammed just days out from Mars based on some of the more interesting findings of its sister ship, Mariner 6. The success of the tandem flight to Mars convinces NASA to adopt a similar mission profile for the upcoming Mars ’71 missions, which will send two Mariner orbiters to take up permanent positions around Mars. NASA and JPL launch Mariner 8, the first of two identical “Mars ’71” orbiters designed to visit Mars. Where previous missions have simply flown past the red planet, Mariners 8 and 9 are intended to put themselves in orbit and remain there to map the majority of the Martian surface. The second stage of the Atlas-Centaur booster used to launch Mariner 8 fails, however, and the robotic Mars explorer crashes into the Atlantic Ocean. Some of its mission objectives are transferred to the identical Mariner 9, due for launch at the end of the month.

NASA and JPL launch Mariner 8, the first of two identical “Mars ’71” orbiters designed to visit Mars. Where previous missions have simply flown past the red planet, Mariners 8 and 9 are intended to put themselves in orbit and remain there to map the majority of the Martian surface. The second stage of the Atlas-Centaur booster used to launch Mariner 8 fails, however, and the robotic Mars explorer crashes into the Atlantic Ocean. Some of its mission objectives are transferred to the identical Mariner 9, due for launch at the end of the month. The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Mariner 9 enters orbit around Mars, becoming the first human spacecraft to orbit another planet in the solar system. The probe begins a nearly year-long survey of the red planet, mapping over 70% of its surface at a much higher resolution than was achieved by the previous NASA Mars probes, Mariners 6 and 7. Mariner 9’s mapping mission is temporarily delayed by a global dust storm obscuring the entire planet when the orbiter arrives. Among its discoveries are Olympus Mons, the solar system’s largest volcano, and the gigantic canyon later named Valles Marineris. Mariner 9 also gathers images of Mars’ two moons, Phobos and Deimos.

The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Mariner 9 enters orbit around Mars, becoming the first human spacecraft to orbit another planet in the solar system. The probe begins a nearly year-long survey of the red planet, mapping over 70% of its surface at a much higher resolution than was achieved by the previous NASA Mars probes, Mariners 6 and 7. Mariner 9’s mapping mission is temporarily delayed by a global dust storm obscuring the entire planet when the orbiter arrives. Among its discoveries are Olympus Mons, the solar system’s largest volcano, and the gigantic canyon later named Valles Marineris. Mariner 9 also gathers images of Mars’ two moons, Phobos and Deimos. NASA’s Mariner 9 Mars orbiter becomes the first spacecraft to provide relatively close-up images of Mars’ innermost, larger moon, Phobos, from over 3,500 miles away. The irregular shape and heavily cratered surface of Phobos point up its likely origins as an asteroid that long ago came close enough to Mars to be captured into an orbit. Phobos (and its still unseen-at-close-range smaller sibling, Deimos) will be imaged at much closer range later in the 1970s by the Viking orbiters.

NASA’s Mariner 9 Mars orbiter becomes the first spacecraft to provide relatively close-up images of Mars’ innermost, larger moon, Phobos, from over 3,500 miles away. The irregular shape and heavily cratered surface of Phobos point up its likely origins as an asteroid that long ago came close enough to Mars to be captured into an orbit. Phobos (and its still unseen-at-close-range smaller sibling, Deimos) will be imaged at much closer range later in the 1970s by the Viking orbiters. The first unmanned space probe to use a gravity assist maneuver to get from one planet to another in a reduced amount of time, Mariner 10 is lauched on a course for the planet Venus, where a carefully planned trajectory allows it to take pictures and measurements at that planet before using Venus’ gravity to fling Mariner 10 inward toward Mercury, allowing it to reach two planets in under two months. It will be the first space probe to visit Mercury.

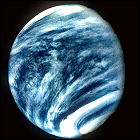

The first unmanned space probe to use a gravity assist maneuver to get from one planet to another in a reduced amount of time, Mariner 10 is lauched on a course for the planet Venus, where a carefully planned trajectory allows it to take pictures and measurements at that planet before using Venus’ gravity to fling Mariner 10 inward toward Mercury, allowing it to reach two planets in under two months. It will be the first space probe to visit Mercury. The unmanned Mariner 10 space probe swings past the planet Venus at a distance of less than 4,000 miles, its cameras capturing a completely opaque sphere whose clouds reveal no surface. But when viewed through ultraviolet filters, Venus suddenly reveals an immense amount of atmospheric detail. Mariner 10’s UV views of Venus are the best images available until the dual Pioneer Venus mission of the late 1970s; meanwhile, Mariner 10 speeds past the planet en route to Mercury.

The unmanned Mariner 10 space probe swings past the planet Venus at a distance of less than 4,000 miles, its cameras capturing a completely opaque sphere whose clouds reveal no surface. But when viewed through ultraviolet filters, Venus suddenly reveals an immense amount of atmospheric detail. Mariner 10’s UV views of Venus are the best images available until the dual Pioneer Venus mission of the late 1970s; meanwhile, Mariner 10 speeds past the planet en route to Mercury. After using the gravity of the larger planet Venus to fling it further toward the sun, NASA’s unmanned space probe Mariner 10 zips by the innermost planet, Mercury, less than 500 miles away from its cratered surface. Its cameras capture the first-ever views of the barren planet, whose surface temperatures vary between frigid on the night side and oven-baked on the hemisphere facing the sun. Mariner 10 passes behind the sun, catching up with Mercury again half a year later.

After using the gravity of the larger planet Venus to fling it further toward the sun, NASA’s unmanned space probe Mariner 10 zips by the innermost planet, Mercury, less than 500 miles away from its cratered surface. Its cameras capture the first-ever views of the barren planet, whose surface temperatures vary between frigid on the night side and oven-baked on the hemisphere facing the sun. Mariner 10 passes behind the sun, catching up with Mercury again half a year later. NASA’s unmanned space probe Mariner 10 makes its second pass of the planet Mercury, six months after its first flyby. This time Mariner passes under the planet’s south pole, getting the first views of that part of Mercury, but barely flying within 30,000 miles of the surface. Once again, following its encounter with Mercury, Mariner 10 slipped into a solar orbit that would bring it back to Mercury several months later.

NASA’s unmanned space probe Mariner 10 makes its second pass of the planet Mercury, six months after its first flyby. This time Mariner passes under the planet’s south pole, getting the first views of that part of Mercury, but barely flying within 30,000 miles of the surface. Once again, following its encounter with Mercury, Mariner 10 slipped into a solar orbit that would bring it back to Mercury several months later. NASA has to borrow some of its own spare parts back from the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum to begin engineering mock-up work on the unmanned Venus radar mapping probe Magellan. As JPL works on modifications to a backup central bus component left over from the Voyager program, a physical copy of that bus from an engineering backup of the Voyager spacecraft is loaned back to JPL, shipped to Pasadena from Washington, D.C. (This loan saves JPL the trouble of building another replica of the bus, the central hub of the spacecraft containing its computer and electrical systems, which could add significant cost to the preparations.) The real Magellan, due to be launched soon after the currently grounded space shuttle program resumes, will cut costs by incorporating unused backup equipment from its predecessors, including a Voyager central bus and high-gain antenna, a medium-gain antenna spare from the Mariner missions to Mars, and a Galileo data handling system.

NASA has to borrow some of its own spare parts back from the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum to begin engineering mock-up work on the unmanned Venus radar mapping probe Magellan. As JPL works on modifications to a backup central bus component left over from the Voyager program, a physical copy of that bus from an engineering backup of the Voyager spacecraft is loaned back to JPL, shipped to Pasadena from Washington, D.C. (This loan saves JPL the trouble of building another replica of the bus, the central hub of the spacecraft containing its computer and electrical systems, which could add significant cost to the preparations.) The real Magellan, due to be launched soon after the currently grounded space shuttle program resumes, will cut costs by incorporating unused backup equipment from its predecessors, including a Voyager central bus and high-gain antenna, a medium-gain antenna spare from the Mariner missions to Mars, and a Galileo data handling system. Bradford A. Smith, a research astronomer and former professor of planetary science and astronomy at the University of Arizona, dies at the age of 86 from complications arising from an autoimmune disorder. Smith became a public figure during the peak years of the uncrewed

Bradford A. Smith, a research astronomer and former professor of planetary science and astronomy at the University of Arizona, dies at the age of 86 from complications arising from an autoimmune disorder. Smith became a public figure during the peak years of the uncrewed