IBM announces the IBM 305 RAMAC (Random Access Memory Accounting) mainframe, a computer as large as two refrigerators, containing the new 350 Disk Storage Unit, the world’s first hard disk drive. The nearly-six-foot-high drive consists of a huge metal case surrounding a towering stack of 50 double-sided magnetic platters, adding up to a total capacity of four megabytes. In 1958, IBM will introduce the option to double capacity by adding a second stack of drive platters to the casing. The 305 RAMAC and 350 Disk Storage Unit together weigh over a ton, and are leased to IBM’s clients for $3,200 per month.

IBM announces the IBM 305 RAMAC (Random Access Memory Accounting) mainframe, a computer as large as two refrigerators, containing the new 350 Disk Storage Unit, the world’s first hard disk drive. The nearly-six-foot-high drive consists of a huge metal case surrounding a towering stack of 50 double-sided magnetic platters, adding up to a total capacity of four megabytes. In 1958, IBM will introduce the option to double capacity by adding a second stack of drive platters to the casing. The 305 RAMAC and 350 Disk Storage Unit together weigh over a ton, and are leased to IBM’s clients for $3,200 per month.

Under the direction of President Eisenhower, the U.S. Department of Defense establishes a high-tech think tank, the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), to conduct scientific and technological research with both national security implications and purely for technological advancement. The formation of ARPA is a direct response to the Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite, and in the years ahead ARPA will lay the cornerstone of what will later become known as the Internet, as well as making significant strides in space science, though the space-related part of ARPA’s initial charter will later be transferred to a new agency called NASA. As the Cold War heats up, ARPA will be renamed DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) and its slate of R&D projects will become almost entirely military-oriented.

Under the direction of President Eisenhower, the U.S. Department of Defense establishes a high-tech think tank, the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), to conduct scientific and technological research with both national security implications and purely for technological advancement. The formation of ARPA is a direct response to the Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite, and in the years ahead ARPA will lay the cornerstone of what will later become known as the Internet, as well as making significant strides in space science, though the space-related part of ARPA’s initial charter will later be transferred to a new agency called NASA. As the Cold War heats up, ARPA will be renamed DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) and its slate of R&D projects will become almost entirely military-oriented. Implementing a revolutionary new take on an idea that has existed on paper since the 1940s, recently-hired Texas Instruments engineer Jack Kilby demonstrates the first fully-functional integrated circuit, with all of the electronic components encased in germanium. While the U.S. Air Force immediately places an order for TI’s new integrated circuits, other engineers continue to refine Kilby’s invention, with Fairchild Semiconductor producing ICs encased in silicon. The move to silicon for ICs leads to smaller electronic devices and the development of microcomputer technology.

Implementing a revolutionary new take on an idea that has existed on paper since the 1940s, recently-hired Texas Instruments engineer Jack Kilby demonstrates the first fully-functional integrated circuit, with all of the electronic components encased in germanium. While the U.S. Air Force immediately places an order for TI’s new integrated circuits, other engineers continue to refine Kilby’s invention, with Fairchild Semiconductor producing ICs encased in silicon. The move to silicon for ICs leads to smaller electronic devices and the development of microcomputer technology. The first government contract is issued in the Apollo lunar landing program, as MIT lands the contract to develop the guidance and navigation computer at the heart of the Apollo vehicles. For its day, MIT designed one of the most robust computers that early ’60s technology could squeeze into such a small space; modern digital watches are far more powerful than that computer. The same computer system will be installed in both the command module and the lunar module.

The first government contract is issued in the Apollo lunar landing program, as MIT lands the contract to develop the guidance and navigation computer at the heart of the Apollo vehicles. For its day, MIT designed one of the most robust computers that early ’60s technology could squeeze into such a small space; modern digital watches are far more powerful than that computer. The same computer system will be installed in both the command module and the lunar module. At the 1962 Open House held at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a student programming project is unveiled on the school’s new DEC PCP-1 computer. In an attempt to demonstrate the machine’s real-time processing power in a context that can be understood by the general public, Steve Russell and his cohorts allow visitors to play the first computer game, Spacewar. The product of months of design and hundreds of man-hours of coding, Spacewar allows two players to navigate their way around the gravity of a sun while trying to blow each other to bits (as displayed on a round oscilloscope). Never patented or copyrighted, Spacewar goes on to “inspire” countless copies, including one of the earliest coin-operated arcade video games, Computer Space.

At the 1962 Open House held at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a student programming project is unveiled on the school’s new DEC PCP-1 computer. In an attempt to demonstrate the machine’s real-time processing power in a context that can be understood by the general public, Steve Russell and his cohorts allow visitors to play the first computer game, Spacewar. The product of months of design and hundreds of man-hours of coding, Spacewar allows two players to navigate their way around the gravity of a sun while trying to blow each other to bits (as displayed on a round oscilloscope). Never patented or copyrighted, Spacewar goes on to “inspire” countless copies, including one of the earliest coin-operated arcade video games, Computer Space. Working at General Electric’s New York R&D lab, scientist Nick Holonyak fires up the first working visible-spectrum light-emitting diode, producing a single small red light. (Texas Instruments had already created infrared LEDs the year before.) Too expensive to mass-produce initially, LEDs will become commonplace in calculators and other electronic devices in the 1970s, though more modern variants in the 1990s will lead to a revolution in lighting and display technology, resulting in flat-screen computer monitors and televisions and spinoff technology such as tablet computers and portable telephones with LED-based touchscreens – all unimaginable in

Working at General Electric’s New York R&D lab, scientist Nick Holonyak fires up the first working visible-spectrum light-emitting diode, producing a single small red light. (Texas Instruments had already created infrared LEDs the year before.) Too expensive to mass-produce initially, LEDs will become commonplace in calculators and other electronic devices in the 1970s, though more modern variants in the 1990s will lead to a revolution in lighting and display technology, resulting in flat-screen computer monitors and televisions and spinoff technology such as tablet computers and portable telephones with LED-based touchscreens – all unimaginable in  In the Hillsboro Press-Gazette, ENIAC and UNIVAC co-creator Dr. John Mauchly predicts that there will come “a time when everyone will carry his own personal computer”, even going so far as to anticipate portable “hand computers” used for such tasks as interactive shopping lists. Mauchly’s predictions aren’t 100% accurate, however: by the 21st century, groceries do not arrive via delivery chutes in every home, and he fails to anticipate the use of “hand computers” to access social networks or view amusingly captioned photos of cats.

In the Hillsboro Press-Gazette, ENIAC and UNIVAC co-creator Dr. John Mauchly predicts that there will come “a time when everyone will carry his own personal computer”, even going so far as to anticipate portable “hand computers” used for such tasks as interactive shopping lists. Mauchly’s predictions aren’t 100% accurate, however: by the 21st century, groceries do not arrive via delivery chutes in every home, and he fails to anticipate the use of “hand computers” to access social networks or view amusingly captioned photos of cats. At the Fall Joint Computer Conference held at the San Francisco Convention Center, computer visionary Douglas Englebart demonstrates a collaborative computer system loaded down with groundbreaking technologies: the first computer mouse, driving a point-and-click object-oriented graphical user interface, bitmapped graphics, hypertext, real-time video conferencing, and a live networked collaborative space. Decades later, computer historians give this event – billed in the conference program as “a research center for augmenting human intellect” – a new name: the mother of all demos.

At the Fall Joint Computer Conference held at the San Francisco Convention Center, computer visionary Douglas Englebart demonstrates a collaborative computer system loaded down with groundbreaking technologies: the first computer mouse, driving a point-and-click object-oriented graphical user interface, bitmapped graphics, hypertext, real-time video conferencing, and a live networked collaborative space. Decades later, computer historians give this event – billed in the conference program as “a research center for augmenting human intellect” – a new name: the mother of all demos. This is the observed day of the internet’s birth, actually marking the day that the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency chose the contractor to build the initial nodes and connections of the ARPAnet. Though the internet is ubiquitous from a 21st century perspective, its origins lie in a disquieting Cold-War-era concept of a distributed computer communications network whose operations could continue even if multiple nodes of the network have been disrupted or destroyed. ARPAnet, the forerunner to the modern internet, will become operational on an experimental basis later in 1969.

This is the observed day of the internet’s birth, actually marking the day that the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency chose the contractor to build the initial nodes and connections of the ARPAnet. Though the internet is ubiquitous from a 21st century perspective, its origins lie in a disquieting Cold-War-era concept of a distributed computer communications network whose operations could continue even if multiple nodes of the network have been disrupted or destroyed. ARPAnet, the forerunner to the modern internet, will become operational on an experimental basis later in 1969. Computer engineer and recent MIT graduate Ray Tomlinson, working on the nascent ARPAnet project, adds minor new features to an experimental file transfer protocol and, in so doing, sends the first network e-mail. This first message doesn’t have far to travel – it arrives at another computer terminal in the same room – but it is the beginning of e-mail on ARPANET, a feature which is adopted so widely and so quickly that it accounts for 75% of all ARPANET data traffic just two years later. Tomlinson is also credited for inventing the user@destination e-mail address format.

Computer engineer and recent MIT graduate Ray Tomlinson, working on the nascent ARPAnet project, adds minor new features to an experimental file transfer protocol and, in so doing, sends the first network e-mail. This first message doesn’t have far to travel – it arrives at another computer terminal in the same room – but it is the beginning of e-mail on ARPANET, a feature which is adopted so widely and so quickly that it accounts for 75% of all ARPANET data traffic just two years later. Tomlinson is also credited for inventing the user@destination e-mail address format. IBM introduces the Model 3340 hard disk drive system for its System/370 mainframe computers. Housed in a large casing similar to a combined washer and dryer, this is the birth of modern hard disk technology, with read and write heads integral to the drive itself rather than being mounted on an arm which reaches into the drive casing. The 3340’s removable modules, each containing drive platters and the read/write heads, can be swapped out with other modules containing other drives. IBM ships the 3340 with two maximum storage capacities: 35 megabytes or 70 megabytes; the unit is internally called a Winchester hard drive, a case of a code name that sticks well beyond development. The 3340 is available through 1984.

IBM introduces the Model 3340 hard disk drive system for its System/370 mainframe computers. Housed in a large casing similar to a combined washer and dryer, this is the birth of modern hard disk technology, with read and write heads integral to the drive itself rather than being mounted on an arm which reaches into the drive casing. The 3340’s removable modules, each containing drive platters and the read/write heads, can be swapped out with other modules containing other drives. IBM ships the 3340 with two maximum storage capacities: 35 megabytes or 70 megabytes; the unit is internally called a Winchester hard drive, a case of a code name that sticks well beyond development. The 3340 is available through 1984. Early networked computing pioneers Lee Felsenstein, Efrem Lipkin and Mark Szpakowski open the first public Community Memory terminal at Leopold’s Records in Berkeley, California. With read-only access for free (and a 25-cent charge to add information to the database, which is maintained on a SDS 940 mainframe at TransAmerica Corporation and accessed via 110 baud acoustic modem), the intention is to computerize the popular push-pin-powered public notice board. Other terminals are eventually made available at various locations, but the SDS 940 proves to be inadequate, and this first iteration of the Community Memory Project will eventually be deactivated in January

Early networked computing pioneers Lee Felsenstein, Efrem Lipkin and Mark Szpakowski open the first public Community Memory terminal at Leopold’s Records in Berkeley, California. With read-only access for free (and a 25-cent charge to add information to the database, which is maintained on a SDS 940 mainframe at TransAmerica Corporation and accessed via 110 baud acoustic modem), the intention is to computerize the popular push-pin-powered public notice board. Other terminals are eventually made available at various locations, but the SDS 940 proves to be inadequate, and this first iteration of the Community Memory Project will eventually be deactivated in January  The January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics Magazine goes on sale days before Christmas 1974, with its cover article heralding the arrival of the MITS Altair 8800 microcomputer. The first open-architecture microcomputer, the Altair is available in kit form or fully assembled, with 4K of RAM built around an Intel 8080 processor. Expecting to sell a few hundred kits, MITS founder Ed Roberts finds himself flooded with so many orders that he has to hire additional workers to start catching up with the backlog of purchases, with the time from order to delivery stretching into months. This is the beginning of the modern computer revolution, with companies other than MITS producing peripherals and software for the Altair. The most notable of these third-party vendors is a newly-formed company called Microsoft – a two-man operation founded by Bill Gates and Paul Allen – which produces a working version of the BASIC language for the Altair.

The January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics Magazine goes on sale days before Christmas 1974, with its cover article heralding the arrival of the MITS Altair 8800 microcomputer. The first open-architecture microcomputer, the Altair is available in kit form or fully assembled, with 4K of RAM built around an Intel 8080 processor. Expecting to sell a few hundred kits, MITS founder Ed Roberts finds himself flooded with so many orders that he has to hire additional workers to start catching up with the backlog of purchases, with the time from order to delivery stretching into months. This is the beginning of the modern computer revolution, with companies other than MITS producing peripherals and software for the Altair. The most notable of these third-party vendors is a newly-formed company called Microsoft – a two-man operation founded by Bill Gates and Paul Allen – which produces a working version of the BASIC language for the Altair. Alpex Corporation, an American computer company, files “the ‘555 Patent” for a “television display control apparatus” capable of loading software from ROM chips embedded in swappable cartridges and other media. This patent effectively shifts the infant video game industry from a hardware-based model to a software-based model, and is licensed by Fairchild Semiconductor for the first cartridge-based video game, the Fairchild Video Entertainment System (later known as Channel F), a year later; the resulting sea change forces a sudden reassessment in the R&D departments at Atari and Magnavox, among others. Due to the remarkably broad nature of patent #4026555, Alpex will be able to take nearly every video game manufacturer to court to force them to license the technology from Alpex through the early ’90s. The first major challenge to Alpex’s patent will come from Nintendo in 1986, a case that will eventually make its way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1997 – by which time Alpex will go bankrupt pursuing the case.

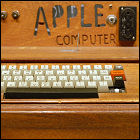

Alpex Corporation, an American computer company, files “the ‘555 Patent” for a “television display control apparatus” capable of loading software from ROM chips embedded in swappable cartridges and other media. This patent effectively shifts the infant video game industry from a hardware-based model to a software-based model, and is licensed by Fairchild Semiconductor for the first cartridge-based video game, the Fairchild Video Entertainment System (later known as Channel F), a year later; the resulting sea change forces a sudden reassessment in the R&D departments at Atari and Magnavox, among others. Due to the remarkably broad nature of patent #4026555, Alpex will be able to take nearly every video game manufacturer to court to force them to license the technology from Alpex through the early ’90s. The first major challenge to Alpex’s patent will come from Nintendo in 1986, a case that will eventually make its way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1997 – by which time Alpex will go bankrupt pursuing the case. The Apple I computer is available for sale, for the price of $666.66, a price set as a practical joke by Apple Computer cofounder Steve Wozniak, who is also the designer of the system’s architecture. The computer is sold as a circuit board, requiring end users to construct their own enclosure to protect it (the elaborate wood casing shown here was neither typical nor standard-issue). Wozniak’s ambitions for an expandable system are built into the Apple I, including add-on memory cards that can expand its native 4K of memory to as much as 48K, with an interface for an optional cassette data storage system. Nearly 200 units are built and sold, but Apple will recall them, offering users an opportunity to upgrade to the Apple II upon that system’s introduction the following year.

The Apple I computer is available for sale, for the price of $666.66, a price set as a practical joke by Apple Computer cofounder Steve Wozniak, who is also the designer of the system’s architecture. The computer is sold as a circuit board, requiring end users to construct their own enclosure to protect it (the elaborate wood casing shown here was neither typical nor standard-issue). Wozniak’s ambitions for an expandable system are built into the Apple I, including add-on memory cards that can expand its native 4K of memory to as much as 48K, with an interface for an optional cassette data storage system. Nearly 200 units are built and sold, but Apple will recall them, offering users an opportunity to upgrade to the Apple II upon that system’s introduction the following year.

Programmers Ward Christensen and Randy Suess put their brainchild, the CBBS or Computer Bulletin Board System, online for the first time. Accessible to anyone with a computer modem and a phone line, CBBS allows users to log in one at a time since the system is limited to a single phone line; messages both public and private can be posted. Christensen and Suess become the first SysOps, or System Operators, responsible for both technical maintenance and moderation of the system’s content. Similar bulletin board systems spring up across America and elsewhere (indeed, in the late 1980s, theLogBook itself will be launched as a series of text files on such a BBS).

Programmers Ward Christensen and Randy Suess put their brainchild, the CBBS or Computer Bulletin Board System, online for the first time. Accessible to anyone with a computer modem and a phone line, CBBS allows users to log in one at a time since the system is limited to a single phone line; messages both public and private can be posted. Christensen and Suess become the first SysOps, or System Operators, responsible for both technical maintenance and moderation of the system’s content. Similar bulletin board systems spring up across America and elsewhere (indeed, in the late 1980s, theLogBook itself will be launched as a series of text files on such a BBS).

Corvus Systems introduces its Winchester hard disk drive for the Apple II computer, available with five or ten megabytes of storage. A bulky device requiring its own power supply independent of the computer to which it’s connected, the Winchester drive carries a $5,000 price tag and an unconventional data backup system, Corvus Mirror, which uses videocassettes (also a fairly new technology). As the investment in this new mass storage technology is fairly daunting, Corvus will introduce a networking system the following year to allow multiple computers access to a single hard drive.

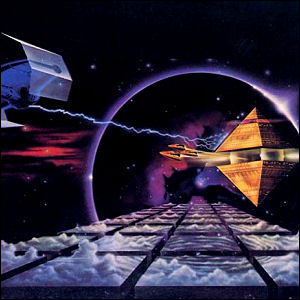

Corvus Systems introduces its Winchester hard disk drive for the Apple II computer, available with five or ten megabytes of storage. A bulky device requiring its own power supply independent of the computer to which it’s connected, the Winchester drive carries a $5,000 price tag and an unconventional data backup system, Corvus Mirror, which uses videocassettes (also a fairly new technology). As the investment in this new mass storage technology is fairly daunting, Corvus will introduce a networking system the following year to allow multiple computers access to a single hard drive. Atari releases the computer game Star Raiders for the Atari 400 and 800 home computer systems, programmed by Doug Neubauer. This is a very early example of a game in the first-person “cockpit” space shooter genre gaining wide popularity.

Atari releases the computer game Star Raiders for the Atari 400 and 800 home computer systems, programmed by Doug Neubauer. This is a very early example of a game in the first-person “cockpit” space shooter genre gaining wide popularity.

Microsoft enters the computer hardware business with a Z80 processor card for the Apple II computer. This peripheral allows the Apple II to run the CP/M operating system and Microsoft BASIC (the Apple II is well on its way to dominating the home computer market at this point). Selling it for nearly $350 is responsible for bringing in the bulk of Microsoft’s revenue between now and the introduction of Microsoft DOS for the IBM PC.

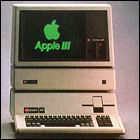

Microsoft enters the computer hardware business with a Z80 processor card for the Apple II computer. This peripheral allows the Apple II to run the CP/M operating system and Microsoft BASIC (the Apple II is well on its way to dominating the home computer market at this point). Selling it for nearly $350 is responsible for bringing in the bulk of Microsoft’s revenue between now and the introduction of Microsoft DOS for the IBM PC. Apple Computer introduces the newest upgrade of its Apple II architecture, the oversized Apple III computer, aimed squarely at the business computing market that Apple has stumbled into as a result of VisiCalc‘s success. The monolithic machine suffers from technical problems from the outset, resulting in recalls and repairs to most early adopters’ Apple III units. With barely 100,000 units sold over three years, Apple pulls the Apple III off the market before 1984 is out.

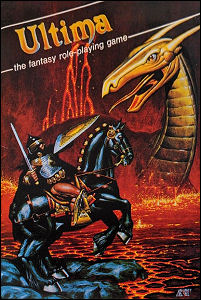

Apple Computer introduces the newest upgrade of its Apple II architecture, the oversized Apple III computer, aimed squarely at the business computing market that Apple has stumbled into as a result of VisiCalc‘s success. The monolithic machine suffers from technical problems from the outset, resulting in recalls and repairs to most early adopters’ Apple III units. With barely 100,000 units sold over three years, Apple pulls the Apple III off the market before 1984 is out. California Pacific Computer releases the computer role playing game game

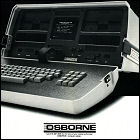

California Pacific Computer releases the computer role playing game game  The Osborne One portable computer is given its public debut at the West Coast Computer Faire in San Francisco. Despite being billed as “portable”, the computer is huge – packing 5¼” floppy disk drives and a tiny CRT monitor and a full-sized keyboard into a suitcase-sized enclosure, it weighs at least 30 pounds. The Osborne I’s native operating system is CP/M.

The Osborne One portable computer is given its public debut at the West Coast Computer Faire in San Francisco. Despite being billed as “portable”, the computer is huge – packing 5¼” floppy disk drives and a tiny CRT monitor and a full-sized keyboard into a suitcase-sized enclosure, it weighs at least 30 pounds. The Osborne I’s native operating system is CP/M. IBM Model 5150, developed under the code name “Chess” but better known as the IBM Personal Computer, is released, including the original PC edition of Microsoft’s MS-DOS. This not only marks the ascendency of Microsoft as a maker of operating systems, but a sudden shift away from a multitude of other computer platforms (especially the Apple II series) toward the IBM PC. Within a year, the first IBM PC-compatible machine will arrive on the market, but while that begins to cost IBM its hardware market share, it popularizes the Intel-8088-based architecture and makes it the standard of the computer industry.

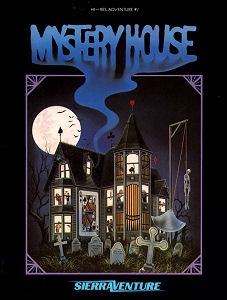

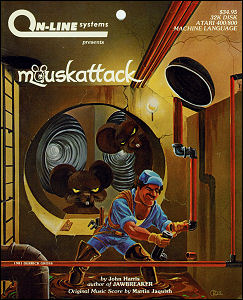

IBM Model 5150, developed under the code name “Chess” but better known as the IBM Personal Computer, is released, including the original PC edition of Microsoft’s MS-DOS. This not only marks the ascendency of Microsoft as a maker of operating systems, but a sudden shift away from a multitude of other computer platforms (especially the Apple II series) toward the IBM PC. Within a year, the first IBM PC-compatible machine will arrive on the market, but while that begins to cost IBM its hardware market share, it popularizes the Intel-8088-based architecture and makes it the standard of the computer industry. Sierra On-Line releases the computer game

Sierra On-Line releases the computer game