The United States Army, and a retinue of scientists who have participated in the top-secret Manhattan Project to create a workable atomic bomb before the then-hostile governments of Germany or Japan can do so, carry out the first detonation of a nuclear weapon in human history, generating a massive explosion with a yield of 22 kilotons of TNT. This is the final test before the deployment of two nuclear weapons in the United States’ war with Japan mere weeks later. Manhattan Project scientists present to witness the test include Robert Oppenheimer, Richard Feynman, Enrico Fermi, and John von Neumann.

The United States Army, and a retinue of scientists who have participated in the top-secret Manhattan Project to create a workable atomic bomb before the then-hostile governments of Germany or Japan can do so, carry out the first detonation of a nuclear weapon in human history, generating a massive explosion with a yield of 22 kilotons of TNT. This is the final test before the deployment of two nuclear weapons in the United States’ war with Japan mere weeks later. Manhattan Project scientists present to witness the test include Robert Oppenheimer, Richard Feynman, Enrico Fermi, and John von Neumann.

After Germany’s surrender, ending the European hostilities in World War II, American military forces embark on a program to recruit captured German scientists, particularly those involved in the development of rockets and missiles, to perform further research and development in these areas for the United States, especially with the Pacific war between the United States and Japan still very much an active concern. The German scientists are also interrogated to find out if any of their technology has been shared with Japan. Numerous German rocket scientists, notably Wernher von Braun and Eberhard Rees, are identified as possible assets to the American war effort despite their past affiliations with Germany’s Nazi regime.

After Germany’s surrender, ending the European hostilities in World War II, American military forces embark on a program to recruit captured German scientists, particularly those involved in the development of rockets and missiles, to perform further research and development in these areas for the United States, especially with the Pacific war between the United States and Japan still very much an active concern. The German scientists are also interrogated to find out if any of their technology has been shared with Japan. Numerous German rocket scientists, notably Wernher von Braun and Eberhard Rees, are identified as possible assets to the American war effort despite their past affiliations with Germany’s Nazi regime. President Truman signs the Atomic Energy Act into law, laying the groundwork for both future military development of nuclear weapons and a civilian nuclear energy industry, though the latter will take time (and further amendments to the law) to develop. The primary development of the initial version of the law is the founding of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, a civilian agency intended to lead both areas of development (and intended to take over from the scientists who, up until now, had been operating in secret as part of the Manhattan Project). Over time, the Commission’s responsibilities will grow to include regulation, safety, and disposal of dangerous radioactive material. Major amendments will be made in 1954 under President Eisenhower to encourage the peacetime nuclear power industry to grow.

President Truman signs the Atomic Energy Act into law, laying the groundwork for both future military development of nuclear weapons and a civilian nuclear energy industry, though the latter will take time (and further amendments to the law) to develop. The primary development of the initial version of the law is the founding of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, a civilian agency intended to lead both areas of development (and intended to take over from the scientists who, up until now, had been operating in secret as part of the Manhattan Project). Over time, the Commission’s responsibilities will grow to include regulation, safety, and disposal of dangerous radioactive material. Major amendments will be made in 1954 under President Eisenhower to encourage the peacetime nuclear power industry to grow. President Truman, after months of weighing the pros and cons of offering amnesty to many of the German scientists involved in the V2 rocket program, signs off on Operation Paperclip, a project to repatriate those scientists to the United States. The initial estimate is that a thousand German scientists will be brought to the U.S., but over time the total will grow closer to 2,000, bringing well over 3,000 family members with them. Wernher von Braun and Hermann Oberth are among the scientists and engineers who accept the offer to work for the U.S., and their efforts, while they do have military value, will form the core of the nascent U.S. space program, with von Braun eventually designing the Saturn V rocket that will take future astronauts to the moon. The Soviet Union mounts a similar program in the weeks to come, attempting to repatriate German scientists and engineers to continue their rocketry research for the Soviets.

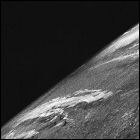

President Truman, after months of weighing the pros and cons of offering amnesty to many of the German scientists involved in the V2 rocket program, signs off on Operation Paperclip, a project to repatriate those scientists to the United States. The initial estimate is that a thousand German scientists will be brought to the U.S., but over time the total will grow closer to 2,000, bringing well over 3,000 family members with them. Wernher von Braun and Hermann Oberth are among the scientists and engineers who accept the offer to work for the U.S., and their efforts, while they do have military value, will form the core of the nascent U.S. space program, with von Braun eventually designing the Saturn V rocket that will take future astronauts to the moon. The Soviet Union mounts a similar program in the weeks to come, attempting to repatriate German scientists and engineers to continue their rocketry research for the Soviets.  Mounting a 35mm film camera into a captured German V2 rocket launched to an altitude of 65 miles, scientists and engineers at the U.S. Navy’s White Sands Missile Range capture the first photo of Earth from space. (The previous highest-altitude photos taken were from a hot-air balloon in 1935, from an altitude of less than 14 miles, although at that altitude the photos did reveal the curvature of the Earth.) The rocket and camera are destroyed when they fall back to Earth, but the reinforced film cartridge survives. This is the first of many such experimental flights carried out at White Sands.

Mounting a 35mm film camera into a captured German V2 rocket launched to an altitude of 65 miles, scientists and engineers at the U.S. Navy’s White Sands Missile Range capture the first photo of Earth from space. (The previous highest-altitude photos taken were from a hot-air balloon in 1935, from an altitude of less than 14 miles, although at that altitude the photos did reveal the curvature of the Earth.) The rocket and camera are destroyed when they fall back to Earth, but the reinforced film cartridge survives. This is the first of many such experimental flights carried out at White Sands. Continuing experimental photography from captured German V2 rockets, scientists and engineers at the U.S. Army’s White Sands Missile Range capture a view of Earth from space at an altitude of 100 miles. Though the V2 is capable only of ballistic suborbital flight, an automated camera on the rocket captures the curve of the Earth before falling back to the surface. As with earlier experimental unmanned flights in 1946, also using captured V2 rockets, the rocket and camera are destroyed upon impact with the ground.

Continuing experimental photography from captured German V2 rockets, scientists and engineers at the U.S. Army’s White Sands Missile Range capture a view of Earth from space at an altitude of 100 miles. Though the V2 is capable only of ballistic suborbital flight, an automated camera on the rocket captures the curve of the Earth before falling back to the surface. As with earlier experimental unmanned flights in 1946, also using captured V2 rockets, the rocket and camera are destroyed upon impact with the ground. The first-ever American-made science fiction television series, Captain Video And His Video Rangers, debuts on the DuMont Television Network. Originated live from a studio in New York City, the series is aimed squarely at younger viewers, but in years to come the show will enjoy scripts written by such science fiction luminaries as Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Jack Vance, Robert Sheckley, and James Blish. The series runs five nights a week for six years.

The first-ever American-made science fiction television series, Captain Video And His Video Rangers, debuts on the DuMont Television Network. Originated live from a studio in New York City, the series is aimed squarely at younger viewers, but in years to come the show will enjoy scripts written by such science fiction luminaries as Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Jack Vance, Robert Sheckley, and James Blish. The series runs five nights a week for six years. The Soviet Union detonates its first nuclear weapon, internally code named RDS-1, near a specially-built “dummy” village which includes various structures, aircraft and other military hardware, and livestock, all present to test the effects of an atomic weapon detonation in their vicinity. Western intelligence is caught off guard when the radioactive fallout is picked up by detection equipment on weather reconnaissance flights between Japan and Alaska, as the Soviets were not expected to have their own nuclear weapons until sometime in the 1950s. This is a turning point in the Cold War, initiating the race toward the next evolution of nuclear weapons: the hydrogen, or thermonuclear, bomb.

The Soviet Union detonates its first nuclear weapon, internally code named RDS-1, near a specially-built “dummy” village which includes various structures, aircraft and other military hardware, and livestock, all present to test the effects of an atomic weapon detonation in their vicinity. Western intelligence is caught off guard when the radioactive fallout is picked up by detection equipment on weather reconnaissance flights between Japan and Alaska, as the Soviets were not expected to have their own nuclear weapons until sometime in the 1950s. This is a turning point in the Cold War, initiating the race toward the next evolution of nuclear weapons: the hydrogen, or thermonuclear, bomb. The A.C. Nielsen Company publishes its first-ever television ratings in the United States, compiling data collected over a “sweep month” running from early April through early May of 1950. The top TV program at the time, according to Nielsen’s data gathering, is Milton Berle’s Texaco Star Theater. The Nielsen ratings and data collection methodology will attract controversy for decades to come, and will spell doom for many shows with small but loyal followings.

The A.C. Nielsen Company publishes its first-ever television ratings in the United States, compiling data collected over a “sweep month” running from early April through early May of 1950. The top TV program at the time, according to Nielsen’s data gathering, is Milton Berle’s Texaco Star Theater. The Nielsen ratings and data collection methodology will attract controversy for decades to come, and will spell doom for many shows with small but loyal followings. The first episode of ABC’s science fiction anthology series, Tales Of Tomorrow, premieres on ABC, with each episode’s opening titles proclaiming that the series is produced “in cooperation with the Science-Fiction League of America”, a collective of sci-fi writers including Isaac Asimov and Theodore Sturgeon among its members. This episode, written by Sturgeon himself, stars Lon McCallister and Martin Brandt.

The first episode of ABC’s science fiction anthology series, Tales Of Tomorrow, premieres on ABC, with each episode’s opening titles proclaiming that the series is produced “in cooperation with the Science-Fiction League of America”, a collective of sci-fi writers including Isaac Asimov and Theodore Sturgeon among its members. This episode, written by Sturgeon himself, stars Lon McCallister and Martin Brandt. Using a telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory, astronomer Seth Nicholson discovers Ananke, a tiny moon of Jupiter orbiting the huge planet at an average distance of 21 million miles and at a high inclination relative to Jupiter’s equator. Ananke is most likely a captured asteroid or the remnant of a captured asteroid, and other small Jovian moons in the same orbit may be other pieces of the captured (and shredded) body. Ananke is the first Jovian moon discovered in nearly two decades, and it will be over two more decades before another is found.

Using a telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory, astronomer Seth Nicholson discovers Ananke, a tiny moon of Jupiter orbiting the huge planet at an average distance of 21 million miles and at a high inclination relative to Jupiter’s equator. Ananke is most likely a captured asteroid or the remnant of a captured asteroid, and other small Jovian moons in the same orbit may be other pieces of the captured (and shredded) body. Ananke is the first Jovian moon discovered in nearly two decades, and it will be over two more decades before another is found. The U.S. Weather bureau signs on radio station KWO35, located at New York’s La Guardia Airport, broadcasting weather forecasts primarily for the benefit of pilots. Not targeted for public consumption, the experimental station broadcasts for several hours a day at a frequency of 162.55Mhz, outside of the spectrum reserved for FM radio. A similar station on the same frequency will later sign on at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport in 1953, again mainly for the consumption of airline pilots. Marine forecasts are added later, and the system helps the Weather Bureau prevent its local forecasters from being overwhelmed by requests for “personalized” weather reports for pilots. These two stations are the precursor for the nationwide weather radio network operated by the Weather Bureau’s successor agency, the National Weather Service.

The U.S. Weather bureau signs on radio station KWO35, located at New York’s La Guardia Airport, broadcasting weather forecasts primarily for the benefit of pilots. Not targeted for public consumption, the experimental station broadcasts for several hours a day at a frequency of 162.55Mhz, outside of the spectrum reserved for FM radio. A similar station on the same frequency will later sign on at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport in 1953, again mainly for the consumption of airline pilots. Marine forecasts are added later, and the system helps the Weather Bureau prevent its local forecasters from being overwhelmed by requests for “personalized” weather reports for pilots. These two stations are the precursor for the nationwide weather radio network operated by the Weather Bureau’s successor agency, the National Weather Service. As a response to early Soviet atomic weapon tests, President Truman orders the initiation of the nationwide CONELRAD (Control of Electromagnetic Radiation) system, designed to limit the number of actively broadcasting radio stations whose signals could be used by enemy bombers to home in on and attack population centers. Designated AM radio stations would pass along emergency signals to smaller stations downstream, which would then begin a complex cycle of broadcasting emergency information to the public and then shutting down to allow another station to broadcast the same information; it is hoped that the rapidly shifting radio signals will prevent an invading enemy from finding viable targets. With its operating strategy assuming nuclear-armed Soviet bombers, CONELRAD will be rendered obsolete by the rise of the intercontinental ballistic missile by the end of the decade, and will be replaced by the Emergency Broadcast system in 1963.

As a response to early Soviet atomic weapon tests, President Truman orders the initiation of the nationwide CONELRAD (Control of Electromagnetic Radiation) system, designed to limit the number of actively broadcasting radio stations whose signals could be used by enemy bombers to home in on and attack population centers. Designated AM radio stations would pass along emergency signals to smaller stations downstream, which would then begin a complex cycle of broadcasting emergency information to the public and then shutting down to allow another station to broadcast the same information; it is hoped that the rapidly shifting radio signals will prevent an invading enemy from finding viable targets. With its operating strategy assuming nuclear-armed Soviet bombers, CONELRAD will be rendered obsolete by the rise of the intercontinental ballistic missile by the end of the decade, and will be replaced by the Emergency Broadcast system in 1963.