SwordQuest: Earthworld

The Game: As a lone adventurer, you wander through the labyrinthine expanses of an underground dungeon in search of a lost treasure. You must cross Frogger-esque screens of fast-moving logs, avoid rooms full of deadly spears which will only kill you just enough to drop-kick your sorry butt back to the bottom of the screen, and enjoy the full capabilities of the Atari 2600’s ability to generate varying frequencies of white noise. (Atari, 1982)

The Game: As a lone adventurer, you wander through the labyrinthine expanses of an underground dungeon in search of a lost treasure. You must cross Frogger-esque screens of fast-moving logs, avoid rooms full of deadly spears which will only kill you just enough to drop-kick your sorry butt back to the bottom of the screen, and enjoy the full capabilities of the Atari 2600’s ability to generate varying frequencies of white noise. (Atari, 1982)

Memories: One of the handful of debacles that marked the change in Atari‘s fortunes, the SwordQuest series was a very heavily-hyped four-game saga which tried to break new ground in the adventure genre for the 2600 console. Sadly, it didn’t even get close to breaking ground, or even wind for that matter – the fourth title, Airworld, was never released. Supposedly, the winners of each of the first three games would compete for a bejewelled prize and the opportunity to reconvene for a tournament to complete the fourth game first and win a wildly expensive sword.

Shark Attack

The Game: You’re a deep-sea diver in search of treasure under the ocean. There are only a couple of problems though – there’s a maze made of messy seaweed, which can slow you down or even trap you until you work your way free of it. And if that’s not enough of a problem, these waters are shark-infested, meaning that getting stuck in the path of a finned foe could mean your finish. (Games By Apollo, 1982)

The Game: You’re a deep-sea diver in search of treasure under the ocean. There are only a couple of problems though – there’s a maze made of messy seaweed, which can slow you down or even trap you until you work your way free of it. And if that’s not enough of a problem, these waters are shark-infested, meaning that getting stuck in the path of a finned foe could mean your finish. (Games By Apollo, 1982)

Memories: A very thinly-disguised Pac-Man ripoff (the “treasures” are just dots, need I say more?), Shark Attack‘s storied history is more interesting than the game itself.

Pac-Man

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots and evading four monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period. (Atari, 1982)

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots and evading four monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period. (Atari, 1982)

Memories: It all began with the arrival of the Pac-Man arcade game in 1980. Pac-Man was guzzling millions of quarters and generating a licensing and merchandising firestorm. Numerous home video game companies bid for the rights to the game, and you have to understand, bidding for the rights to produce the home video game version of Pac-Man was like bidding for the toy rights for the next Star Wars movie – very expensive and very high-profile. Money was flying fast and furious. Atari won.

Pac-Man

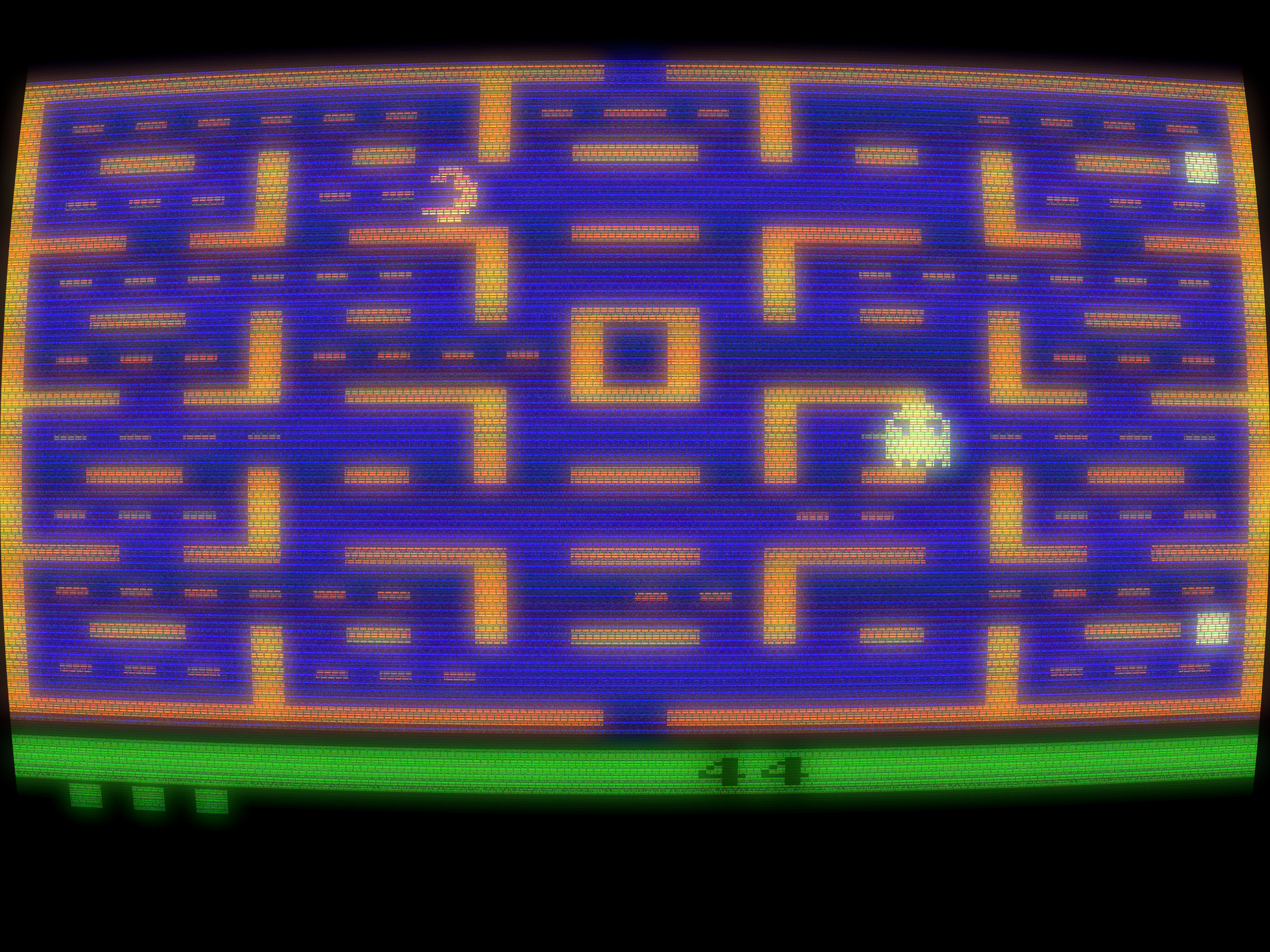

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots and evading four colorful monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period for an escalating score . Periodically, assorted items appear near the center of the maze, and you can consume these for additional points as well. The monsters, once eaten, return to their home base in ghost form and return to chase you anew. If cleared of dots, the maze refills and the game starts again, but just a little bit faster… (Atari, 1982)

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots and evading four colorful monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period for an escalating score . Periodically, assorted items appear near the center of the maze, and you can consume these for additional points as well. The monsters, once eaten, return to their home base in ghost form and return to chase you anew. If cleared of dots, the maze refills and the game starts again, but just a little bit faster… (Atari, 1982)

Memories: In the war of the second-generation consoles, it was clear what the chief ammunition would be: immensely popular arcade game licenses. The ColecoVision jumped out of the gates with Donkey Kong as a pack-in title, and Atari – already fighting bad word-of-mouth criticism of the 5200’s lackluster joysticks – would have to give the SuperSystem something a little more compelling than its cousin 2600’s Combat pack-in. But then, of course, everyone already knew that Atari held that most precious of arcade licenses in the early 80s, Pac-Man.

Pepper II

The Game: You’re a little angel (of sorts). You run around a maze consisting of zippers which close or open, depending upon whether or not you’ve already gone over that section of the maze. Zipping up one square of the maze scores points for you, but it gets trickier. Little devils chase you around the maze, trying to kill you before you can zip up the entire screen. If you zip up enough of the maze and grab a power-pellet-like object, you can dispatch some of your pursuers. Clear the screen and the fun begins anew. (Exidy, 1982)

The Game: You’re a little angel (of sorts). You run around a maze consisting of zippers which close or open, depending upon whether or not you’ve already gone over that section of the maze. Zipping up one square of the maze scores points for you, but it gets trickier. Little devils chase you around the maze, trying to kill you before you can zip up the entire screen. If you zip up enough of the maze and grab a power-pellet-like object, you can dispatch some of your pursuers. Clear the screen and the fun begins anew. (Exidy, 1982)

Memories: One of the first games released for Colecovision, Pepper II lived up to the advertising hype that basically said that owning Coleco’s new console was as good as having your own arcade. While the original arcade game didn’t exactly set the bar very high for any home adaptations, Pepper II really sells the Colecovision = arcade message by being almost flawless.

Night Stalker

The Game: You’re alone, unarmed, in a maze full of bats, bugs and ‘bots, most of whom can kill you on contact (though the robots would happily shoot you rather than catching up with you). Loaded guns appear periodically, giving you a limited number of rounds with which to take out some of these creepy foes, though your shots are best reserved for the robots and the spiders, who have a slightly more malicious intent toward you than the bats. If you shoot the bats, others will appear to take their place. If you shoot the ‘bots, the same thing happens, only a faster, sharper-shooting model rolls out every time. Your best bet is to stay on the move, stay armed, conserve your firepower – and don’t be afraid to head back to your safe room at the center of the screen. (Mattel Electronics, 1982)

The Game: You’re alone, unarmed, in a maze full of bats, bugs and ‘bots, most of whom can kill you on contact (though the robots would happily shoot you rather than catching up with you). Loaded guns appear periodically, giving you a limited number of rounds with which to take out some of these creepy foes, though your shots are best reserved for the robots and the spiders, who have a slightly more malicious intent toward you than the bats. If you shoot the bats, others will appear to take their place. If you shoot the ‘bots, the same thing happens, only a faster, sharper-shooting model rolls out every time. Your best bet is to stay on the move, stay armed, conserve your firepower – and don’t be afraid to head back to your safe room at the center of the screen. (Mattel Electronics, 1982)

Memories: A devious and nerve-wracking little maze chase of a game, Night Stalker is a great game if you’re up for an endurance contest, but not so much if you’re looking for a game where you actually stand a chance of winning or advancing to a new maze. The playing field you see is the playing field you get, and you’re stuck there – until you die.

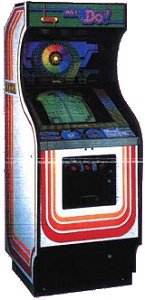

Mr. Do!

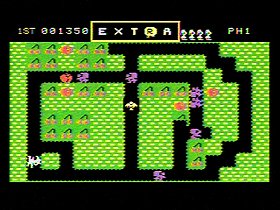

The Game: As an elfin dweller of a magic garden, you must avoid or do away with a bunch of nasty critters who are after you, while gobbling up

The Game: As an elfin dweller of a magic garden, you must avoid or do away with a bunch of nasty critters who are after you, while gobbling up  as much yummy fruit as you can. (Coleco, 1982)

as much yummy fruit as you can. (Coleco, 1982)

Memories: Probably the highest-profile title of Coleco’s original licensing deal with Universal, Mr. Do! came home in an almost insanely entertaining cartridge for the ColecoVision. The graphics and sound closely mimic those of the arcade game, and control seems fairly smooth to me.

Mouse Trap

The Game: In this munching-maze game (one of the dozens of such games which popped up in the wake of Pac-Man), you control a cartoonish mouse who scurries around a cheese-filled maze which can only be navigated by strategically opening and closing doors in the maze. Occasionally a big chunk o’ cheese can be gobbled for extra points. Is it that easy? No. There is also a herd of hungry kitties who would love a mousy morsel. But you’re not defenseless. By eating a bone (the equivalent of Pac-Man’s power pellets), you can transform into a dog, capable of eating the cats. But each bone’s effects only last for a little while, after which you revert to a defenseless mouse. (Coleco, 1982)

The Game: In this munching-maze game (one of the dozens of such games which popped up in the wake of Pac-Man), you control a cartoonish mouse who scurries around a cheese-filled maze which can only be navigated by strategically opening and closing doors in the maze. Occasionally a big chunk o’ cheese can be gobbled for extra points. Is it that easy? No. There is also a herd of hungry kitties who would love a mousy morsel. But you’re not defenseless. By eating a bone (the equivalent of Pac-Man’s power pellets), you can transform into a dog, capable of eating the cats. But each bone’s effects only last for a little while, after which you revert to a defenseless mouse. (Coleco, 1982)

Memories: To some extent, I think regular readers of Phosphor Dot Fossils have come to expect certain things…and the occasional justified slamming of a 2600 game or two is probably one of them. But not this one. No, I’m here to tell you that I love Coleco’s 2600 translation of the obscure Exidy coin-op maze chase Mouse Trap. Yes, seriously!

Mouse Trap

The Game: In this munching-maze game, you control a mouse who scurries around a cheese-filled maze which can only be navigated by strategically opening and closing yellow, red and blue doors with their color-coded buttons. Occasionally a big chunk o’ cheese can be gobbled for extra points. Is it that easy? No. There is also a herd of hungry kitties who would love a mousy morsel. But you’re not defenseless. By eating a bone, you can transform into a dog, capable of eating the cats. But each bone’s effects only last for a little while, after which you revert to a defenseless mouse. (Coleco, 1982)

The Game: In this munching-maze game, you control a mouse who scurries around a cheese-filled maze which can only be navigated by strategically opening and closing yellow, red and blue doors with their color-coded buttons. Occasionally a big chunk o’ cheese can be gobbled for extra points. Is it that easy? No. There is also a herd of hungry kitties who would love a mousy morsel. But you’re not defenseless. By eating a bone, you can transform into a dog, capable of eating the cats. But each bone’s effects only last for a little while, after which you revert to a defenseless mouse. (Coleco, 1982)

Memories: Based on the almost-obscure Exidy arcade game, Coleco turned out a faithful cartridge version of Mouse Trap, with one drawback – just as it was in the arcade, the control scheme for opening the color-coded doors throughout the maze wasn’t the most intuitive way that anyone had ever come up with for controlling a game, even if one does have the overlays that fit over the controller keypads.

Microsurgeon

The Game: Ready for a fantastic journey? So long as you’re not counting on Raquel Welch riding shotgun with you, this is as close as you’re going to get. You control a tiny robot probe inside the body of a living, breathing human patient who has a lot of health problems. Tar deposits in the lungs, cholesterol clogging the arteries, and rogue infections traveling around messing everything up. And then there’s you – capable of administering targeted doses of ultrasonic sound, antibiotics and aspirin to fix things up. Keep an eye on your patient’s status at all times – and be careful not to wipe out disease-fighting white blood cells which occasionally regard your robot probe as a foreign body and attack it. Just because you don’t get to play doctor with the aforementioned Ms. Welch (ahem – get your mind out of the gutter!) doesn’t mean this won’t be a fun operation. (Imagic, 1982)

The Game: Ready for a fantastic journey? So long as you’re not counting on Raquel Welch riding shotgun with you, this is as close as you’re going to get. You control a tiny robot probe inside the body of a living, breathing human patient who has a lot of health problems. Tar deposits in the lungs, cholesterol clogging the arteries, and rogue infections traveling around messing everything up. And then there’s you – capable of administering targeted doses of ultrasonic sound, antibiotics and aspirin to fix things up. Keep an eye on your patient’s status at all times – and be careful not to wipe out disease-fighting white blood cells which occasionally regard your robot probe as a foreign body and attack it. Just because you don’t get to play doctor with the aforementioned Ms. Welch (ahem – get your mind out of the gutter!) doesn’t mean this won’t be a fun operation. (Imagic, 1982)

Memories: Microsurgeon, designed and programmed by Imagic code wrangler Rick Levine (who even put his signature – as a series of slightly twisted arteries – inside the game’s human body maze), is a perfect example of Imagic’s ability to get the best out of the Intellivision – it’s truly one of those “killer app” games that defines a console.

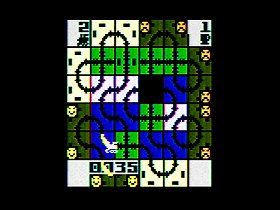

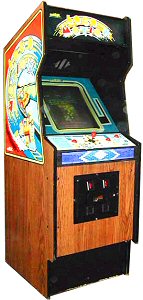

Loco Motion

The Game: A train scoots around a twisty maze of tiles representing overpasses, turns, straightaways and terminals. One portion of the maze is blank, and a train will be lost if it hits that blank tile. You can move the blank tile and one adjacent tile around on the map – even if the train is in transit on that tile – in an effort to keep it moving around the maze, picking up passengers. (Passengers that the train can reach are smiley faces; passengers cut off from the main route are frowning.) If any passengers are cut off for an extended period of time, a monster begins wandering that route, and it’ll cost you a train if it comes in contact with your train. You may have to outrun it with the “speed” button in order to pick up the last passengers and clear the level to move on to a bigger maze. (Mattel [under license from Konami], 1982)

The Game: A train scoots around a twisty maze of tiles representing overpasses, turns, straightaways and terminals. One portion of the maze is blank, and a train will be lost if it hits that blank tile. You can move the blank tile and one adjacent tile around on the map – even if the train is in transit on that tile – in an effort to keep it moving around the maze, picking up passengers. (Passengers that the train can reach are smiley faces; passengers cut off from the main route are frowning.) If any passengers are cut off for an extended period of time, a monster begins wandering that route, and it’ll cost you a train if it comes in contact with your train. You may have to outrun it with the “speed” button in order to pick up the last passengers and clear the level to move on to a bigger maze. (Mattel [under license from Konami], 1982)

Memories: Mattel’s licensed adaptation of the extremely minor arcade hit by Konami is actually, believe it or not, an improvement in some areas on the arcade game. The graphic look isn’t one of those areas, but in a strange way, the Intellivision’s disc controller is more instinctive for the sliding-tile-puzzle game play of Loco Motion.

Lock ‘n’ Chase

The Game: You’re in charge of a getaway car loaded with crafty criminals. Your job is to sneak the crooks around the maze, one at a time, avoid four colorful cops who are hot on your trail, and grab all the dough – and, of course, to escape so you can steal again another day. (Mattel [under license from Data East], 1982)

The Game: You’re in charge of a getaway car loaded with crafty criminals. Your job is to sneak the crooks around the maze, one at a time, avoid four colorful cops who are hot on your trail, and grab all the dough – and, of course, to escape so you can steal again another day. (Mattel [under license from Data East], 1982)

Memories: A fine translation of Data East’s arcade game, this cartridge – one of the earliest examples of a licensed coin-op title from Mattel – is let down by the maddening control problems of the dreaded disc controller. But audiovisually speaking, it was as close as one could get to the original, so I do have to award it some points there.

Lock ‘N’ Chase

The Game: You’re in charge of a getaway car loaded with crafty criminals. Your job is to sneak around the maze, avoid four colorful cops who are hot on your trail, and grab all the dough – and, of course, to escape so you can steal again another day. But the cops can trap you with a series of doors that can prevent you from getting away… (M Network [Mattel Electronics], 1982)

The Game: You’re in charge of a getaway car loaded with crafty criminals. Your job is to sneak around the maze, avoid four colorful cops who are hot on your trail, and grab all the dough – and, of course, to escape so you can steal again another day. But the cops can trap you with a series of doors that can prevent you from getting away… (M Network [Mattel Electronics], 1982)

Memories: 1982. The year that everybody – and I do mean everybody – was trying to build a better Pac-Man. Mattel’s Intellivision console was suffering from the perception among mainstream gamers that the new, next-generation machine lacked arcade titles in its library; with titles like Major League Baseball, Mattel owned the video sports market. But this was 1982 and America had yet to sweat off Pac-Man Fever – sports games weren’t “in” at the moment.

Ladybug

The Game: You’re a hungry ladybug in a maze full of dangers and morsels. Other insects roam the maze trying to eat you, and skulls scattered around the maze are also deadly to the touch. The only advantage you really have is to maneuver skillfully through the revolving doors, slamming them shut behind you and forcing your pursuers to take a different route (they can’t go through the revolving doors). (Coleco, 1982)

The Game: You’re a hungry ladybug in a maze full of dangers and morsels. Other insects roam the maze trying to eat you, and skulls scattered around the maze are also deadly to the touch. The only advantage you really have is to maneuver skillfully through the revolving doors, slamming them shut behind you and forcing your pursuers to take a different route (they can’t go through the revolving doors). (Coleco, 1982)

Memories: With the rights to mega-hits like Pac-Man taken by the time the ColecoVision hit the stores, Coleco grabbed the rights to a number of somewhat more obscure arcade games, including virtually the entire catalog of Universal games, the makers of such games as Mr. Do, Mr. Do’s Castle, and Ladybug. Coleco’s Ladybug cartridge is a very faithful rendition of its arcade inspiration, and it’s quite a bit of fun.

K.C.’s Krazy Chase

The Game: As a small blue spherical creature whose sole sensory organs consist of two eyes, two antennae and an enormous mouth, your mission – should you choose to accept it – is to start munching on the segmented body of the dreaded Dratapillar while avoiding its always-lethal head. When you consume one of its body segments, the Dratapillar’s two henchbeings – known only as Drats – turn white with fright and you can send them a-spinning (normally, they’re deadly to touch too). Eating all of the Dratapillar segments gets you to the next level, and the mayhem begins anew. (North American Philips, 1982)

The Game: As a small blue spherical creature whose sole sensory organs consist of two eyes, two antennae and an enormous mouth, your mission – should you choose to accept it – is to start munching on the segmented body of the dreaded Dratapillar while avoiding its always-lethal head. When you consume one of its body segments, the Dratapillar’s two henchbeings – known only as Drats – turn white with fright and you can send them a-spinning (normally, they’re deadly to touch too). Eating all of the Dratapillar segments gets you to the next level, and the mayhem begins anew. (North American Philips, 1982)

Memories: Perhaps just out of spite, the first non-educational game released to take advantage of the Odyssey 2’s new Voice add-on module featured K.C. Munchkin, the Pac-Man-esque critter who had landed Magnavox on the wrong side of a look-and-feel software lawsuit filed by Atari.

Jungler

The Game: Players control a segmented, centipede-like creature as it wanders through an open maze inhabited by similar creatures. The player’s creature can shoot segments off of the opponent creatures, but the opponents can also turn around and eat their own segments to get out of a corner, which won’t score any points for the player. To clear a level, the player must eliminate the other creatures from the maze. (Emerson [under license from Konami], 1982)

The Game: Players control a segmented, centipede-like creature as it wanders through an open maze inhabited by similar creatures. The player’s creature can shoot segments off of the opponent creatures, but the opponents can also turn around and eat their own segments to get out of a corner, which won’t score any points for the player. To clear a level, the player must eliminate the other creatures from the maze. (Emerson [under license from Konami], 1982)

Memories: 1982 had the dubious distinction of being both the peak year for video gaming, and – arguably – the beginning of the end. That end didn’t play out until the industry crash of 1983 and ’84, but the seeds were planted at least as early as 1982, when the arcade license ruled the home video game roost. Even modest or completely unknown games could command top dollar for home console ports, often in advance of their arcade release, just on the off chance that the licensee was hitching its wagon to the next Pac-Man. Hence… Nibbler.

Jawbreaker

The Game: Ever had a sweet tooth? Now you are the sweet tooth – or teeth, as the case may be. You guide a set of clattering teeth around a mazelike screen of horizontal rows; an opening in each row travels down the wall separating it from the next row. Your job is to eat the tasty treats lining each row until you’ve cleared the screen. Naturally, it’s not just going to be that easy. There are nasty hard candies out to stop you, and they’ll silence those teeth of yours if they catch you – and that just bites. Periodically, a treat appears in the middle of the screen allowing you to turn the tables on them for a brief interval. (Tigervision, 1982)

The Game: Ever had a sweet tooth? Now you are the sweet tooth – or teeth, as the case may be. You guide a set of clattering teeth around a mazelike screen of horizontal rows; an opening in each row travels down the wall separating it from the next row. Your job is to eat the tasty treats lining each row until you’ve cleared the screen. Naturally, it’s not just going to be that easy. There are nasty hard candies out to stop you, and they’ll silence those teeth of yours if they catch you – and that just bites. Periodically, a treat appears in the middle of the screen allowing you to turn the tables on them for a brief interval. (Tigervision, 1982)

Memories: When Atari’s licensed version of Pac-Man hit the store shelves in 1982, it gained an instant notoriety as those looking for the perfect home Pac experience muttered a collective “screw this” and went elsewhere in search of a better game. Tigervision, a subsidiary of Tiger Toys making its first tentative steps into the increasingly-crowded video game arena, gave them that game.

Dark Caverns

The Game: Robots, spiders and critters, oh my! You’re a lone human in a maze teeming with deadly robots, spiders and other nasties, and your trusty gun – which can dispatch any or all of the above – has only a limited amount of ammunition. You can obtain more ammo by walking over a briefly-occurring flashing gun symbol – but until then, if you’re out of ammo, you’re no longer the hunter, but the hunted. (M Network [Mattel], 1982)

The Game: Robots, spiders and critters, oh my! You’re a lone human in a maze teeming with deadly robots, spiders and other nasties, and your trusty gun – which can dispatch any or all of the above – has only a limited amount of ammunition. You can obtain more ammo by walking over a briefly-occurring flashing gun symbol – but until then, if you’re out of ammo, you’re no longer the hunter, but the hunted. (M Network [Mattel], 1982)

Memories: This was the 2600 version of a similar game that Mattel had released for its own Intellivision console (Night Stalker), and it’s fair to say that this edition was just a wee bit simplified.

Clean Sweep

The Game: Years before Robovac and Roomba, there was Clean Sweep, a vacuum cleaner patrolling the vaults of a bank and picking up stray bits of money. (Makes you wonder who programmed it, and who’s emptying the bag!) As you grab more wayward currency, your bag fills up; when you hear an alarm sound, you have to go to the center of the maze to empty your bag and start anew; until you do that, you can’t pick up any more dead presidents. But those aren’t the only alarm bells going off here: things that look alarmingly like huge forceps are chasing you around. If they grab you, it’s your money and your life. There are four corners in the vault that will power up your vacuum cleaner temporarily, enabling you to suck up those forceps and (for a brief while) grab all the cash in your path without filling your bag. Clearing the maze advances you to the next level; losing all your lives leaves the bank wide open. (GCE, 1982)

The Game: Years before Robovac and Roomba, there was Clean Sweep, a vacuum cleaner patrolling the vaults of a bank and picking up stray bits of money. (Makes you wonder who programmed it, and who’s emptying the bag!) As you grab more wayward currency, your bag fills up; when you hear an alarm sound, you have to go to the center of the maze to empty your bag and start anew; until you do that, you can’t pick up any more dead presidents. But those aren’t the only alarm bells going off here: things that look alarmingly like huge forceps are chasing you around. If they grab you, it’s your money and your life. There are four corners in the vault that will power up your vacuum cleaner temporarily, enabling you to suck up those forceps and (for a brief while) grab all the cash in your path without filling your bag. Clearing the maze advances you to the next level; losing all your lives leaves the bank wide open. (GCE, 1982)

Memories: This interesting little take on Pac-Man for the Vectrex is so fun, it’s hard to put down. I’ve been somewhat merciless about Pac-clones in the past, but Clean Sweep shakes things up enough to be fun, making you go back and do things like empty your vacuum bag without really slowing the game down significantly.

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Cartridge

The Game: Your quest begins as you set out from the safety of home to look for adventure in mountainous caverns. When you wander into the dungeons and caverns, your view zooms in to the maze your adventurer is exploring, complete with treasures to collect and deadly dangers to duel. (Mattel Electronics, 1982)

The Game: Your quest begins as you set out from the safety of home to look for adventure in mountainous caverns. When you wander into the dungeons and caverns, your view zooms in to the maze your adventurer is exploring, complete with treasures to collect and deadly dangers to duel. (Mattel Electronics, 1982)

Memories: Combining sword-and-sorcery – traditionally the territory of paper-and-dice role playing games – with video game action has been one of the more inspired mash-ups to come from the golden age of video games. As combinations go, it was almost inevitable – with Dungeons & Dragons being more geeky than mainstream in the 1970s, it was an activity with which game programmers – another geeky crowd – were likely to be acquainted. With all of that crossover going on, it was therefore inevitable that someone, presumably whoever had deep enough pockets to license the title and game elements, would eventually produce an official video game.

Turtles

The Game: You are the Mama Turtle. Your helpless KidTurtles are stuck in a high-rise building, hiding from mean and hungry beetles. The beetles change colors in accordance with their speed and ferocity, from less aggressive green and blue beetles to fast, furious yellow and red beetles. Mama Turtle has to evade the beetles (which are deadly to touch at all times) and touch the mystery squares throughout the maze. The squares could reveal another beetle, or they could reveal one of the KidTurtles. When Mama Turtle picks up a KidTurtle, a safe house appears – usually all the way across the maze – and she must deposit the KidTurtles in the safe house, one at a time. Mama Turtle’s only recourse against the beetles is to lay “bombs” in the maze. Each bomb – and there can only be one on screen at a time – will reduce the first beetle that hits it back to the lowest speed/danger level, buying Mama Turtle a little time. (Mama Turtle can pass over her own bombs harmlessly.) The catch? You only start out with three bombs (is anyone else drawing some grim biological anologies to what Mama Turtle’s “bombs” might be at this point?), and you can replenish your supply of bombs only by running over an occasional flashing symbol which appears at the precise center of the maze…which is usually the most dangerous spot on the screen. Clearing a maze of KidTurtles allows you to climb to the next floor of the building and start anew. (Stern [under license from Konami], 1982)

The Game: You are the Mama Turtle. Your helpless KidTurtles are stuck in a high-rise building, hiding from mean and hungry beetles. The beetles change colors in accordance with their speed and ferocity, from less aggressive green and blue beetles to fast, furious yellow and red beetles. Mama Turtle has to evade the beetles (which are deadly to touch at all times) and touch the mystery squares throughout the maze. The squares could reveal another beetle, or they could reveal one of the KidTurtles. When Mama Turtle picks up a KidTurtle, a safe house appears – usually all the way across the maze – and she must deposit the KidTurtles in the safe house, one at a time. Mama Turtle’s only recourse against the beetles is to lay “bombs” in the maze. Each bomb – and there can only be one on screen at a time – will reduce the first beetle that hits it back to the lowest speed/danger level, buying Mama Turtle a little time. (Mama Turtle can pass over her own bombs harmlessly.) The catch? You only start out with three bombs (is anyone else drawing some grim biological anologies to what Mama Turtle’s “bombs” might be at this point?), and you can replenish your supply of bombs only by running over an occasional flashing symbol which appears at the precise center of the maze…which is usually the most dangerous spot on the screen. Clearing a maze of KidTurtles allows you to climb to the next floor of the building and start anew. (Stern [under license from Konami], 1982)

Memories: Turtles is among the most obscure exponents of the maze chase format to hit the arcade in the early ’80s. I think I saw – maybe – one Turtles arcade game in my life, and it was only there for a few weeks. Actually, though, it’s not a bad game.

Tutankham

The Game: As an intrepid, pith-helmeted explorer, you’re exploring King Tut’s catacombs, which are populated by a variety of killer bugs, birds, and other nasties. You’re capable of firing left and right, but not vertically – so any oncoming threats from above or below must be outrun or avoided. Warp portals will instantly whisk you away to other parts of the maze (though this doesn’t necessarily mean safer). Gathering all of the treasures and keys will allow you to open the vault at the end of each level…which leads to the next, and even more difficult level. It’s like The Mummy, only much more entertaining. (Stern, 1982)

The Game: As an intrepid, pith-helmeted explorer, you’re exploring King Tut’s catacombs, which are populated by a variety of killer bugs, birds, and other nasties. You’re capable of firing left and right, but not vertically – so any oncoming threats from above or below must be outrun or avoided. Warp portals will instantly whisk you away to other parts of the maze (though this doesn’t necessarily mean safer). Gathering all of the treasures and keys will allow you to open the vault at the end of each level…which leads to the next, and even more difficult level. It’s like The Mummy, only much more entertaining. (Stern, 1982)

Memories: Konami/Stern’s 1982 maze shooter was about as different from its antecedents (Berzerk and Frenzy) as possible, and was still fun. The one thing that always got people in the arcades, especially on their first attempt at playing the game, was the fact that it was impossible to shoot vertically – firing could be controlled by a second joystick limited to left-right movement.

Tron

The Game: Based on the most computerized movie of its era, the Tron arcade game puts you in the role of the eponymous video warrior in a variety of contests. In the Grid Bug game, you must eliminate as many grid bugs (who are naturally deadly to the touch) as possible and enter the I/O tower safely before the fast-moving timer hits zero. The maddening Light Cycle game was the only stage to directly correspond with the movie. You and your opponent face off in super-fast Light Cycles, which leave solid walls in their wake. You must not collide with the computer’s Light Cycle, its solid trail, or the walls of the arena. To win, you must trap the other Light Cycle(s) (in later stages, you face three opponents) within the solid wake of your own vehicle. The MCP game is basically a simple version of Breakout, but the wall of colors rotated counter-clockwise, threatening to trap you if you made a run for it through a small gap. The Tank game is a tricky chase through a twisty maze, where you try to blast opposing tank(s) three times each…while they need to score only one hit on your tank to put you out of commission. (Bally/Midway, 1982)

The Game: Based on the most computerized movie of its era, the Tron arcade game puts you in the role of the eponymous video warrior in a variety of contests. In the Grid Bug game, you must eliminate as many grid bugs (who are naturally deadly to the touch) as possible and enter the I/O tower safely before the fast-moving timer hits zero. The maddening Light Cycle game was the only stage to directly correspond with the movie. You and your opponent face off in super-fast Light Cycles, which leave solid walls in their wake. You must not collide with the computer’s Light Cycle, its solid trail, or the walls of the arena. To win, you must trap the other Light Cycle(s) (in later stages, you face three opponents) within the solid wake of your own vehicle. The MCP game is basically a simple version of Breakout, but the wall of colors rotated counter-clockwise, threatening to trap you if you made a run for it through a small gap. The Tank game is a tricky chase through a twisty maze, where you try to blast opposing tank(s) three times each…while they need to score only one hit on your tank to put you out of commission. (Bally/Midway, 1982)

Memories: Okay, granted, so there really isn’t much correlation between Tron the game and Tron the movie, but in this case, it doesn’t matter. The game, with its awesome backlit cabinet graphics of special effects stills from the movie successfully, stole just enough of the movie’s millieu to be a successful tie-in – and let’s not forget the awesome polyphonic recreation of Wendy Carlos’ cool synthesized score from the movie, which was heard mainly during the Grid Bug game.

Time Tunnel

The Game: As the conductor of a time-traveling train, you must find and collect your passenger cars in the present day, move on to the near future to pull up to several stations and fill those cars with time travelers, and then deposit them at various attractions in the distant future. That would be difficult enough to do without running out of fuel, but you also have to contend with space creatures and repeatedly avoid collisions with a competing train by controlling the switches on the tracks. (1982, Taito)

The Game: As the conductor of a time-traveling train, you must find and collect your passenger cars in the present day, move on to the near future to pull up to several stations and fill those cars with time travelers, and then deposit them at various attractions in the distant future. That would be difficult enough to do without running out of fuel, but you also have to contend with space creatures and repeatedly avoid collisions with a competing train by controlling the switches on the tracks. (1982, Taito)

Memories: This exceedingly obscure Taito arcade game is cute and innovative – it’s certainly not another riff on Loco-Motion, that’s for sure. But if you don’t remember it, there may be a reason – it takes several minutes to play a single game. This in and of itself is not a bad thing, but the very nature of arcade games is to vanquish as many challengers as possible, and quickly – the more people come back to play an arcade game, the more money it earns, so conventional wisdom among arcade operators in the 1980s was to dispense quickly with any game that didn’t chew through players’ quarters quickly. A game that took a long time to play had limited earning potential, three words that could get an arcade game scrapped, sent back to the distributor, or converted into another game in record time.

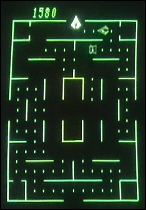

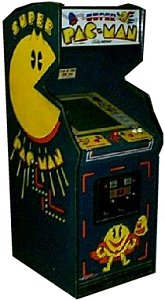

Super Pac-Man

The Game: Once again, Pac-Man roams the maze, pursued by four colorful ghosts. But instead of dots, this maze is peppered with other goodies, ranging from the usual fruits (apples, bananas, etc.) to donuts, cake, and burgers. And in addition to the traditional four “power pellets” in each corner of the screen, there are two green “super power pellets” per screen, which give the mighty yellow one the power to fly over the monsters’ heads and to break down doors that confine some of the yummy treats in the maze. (Bally/Midway [under license from Namco], 1982)

The Game: Once again, Pac-Man roams the maze, pursued by four colorful ghosts. But instead of dots, this maze is peppered with other goodies, ranging from the usual fruits (apples, bananas, etc.) to donuts, cake, and burgers. And in addition to the traditional four “power pellets” in each corner of the screen, there are two green “super power pellets” per screen, which give the mighty yellow one the power to fly over the monsters’ heads and to break down doors that confine some of the yummy treats in the maze. (Bally/Midway [under license from Namco], 1982)

Memories: The earliest of several very strange departures from the successful Pac-Man formula, Super Pac-Man was still a fun and, more often than not, fondly remembered game, even if it was ever so slightly baffling. Admittedly, even the mention above of Pac-Man flying is my own interpretation, based on the Pac-Man-going-on-Superman artwork on the arcade cabinet. It’s a bizarre little concept!

Pengo

The Game: As a cute, fuzzy, harmless little penguin, you roam around an enclosed maze of ice blocks. If this sounds too good to be true – especially for a polar-dwelling avian life form – that’s because you’re not the only critter waddling around in the frozen tundra. Killer Sno-Bees chase little Pengo around the ice, and if they catch up to him and sting him, it’ll cost you a life. But your little flightless waterfowl isn’t completely defenseless. Pengo can push blocks of ice out of the maze, changing the configuration of the playing field and squashing Sno-Bees with a well-timed shove. Clearing the field of Sno-Bees allows you to advance to the next level. (Sega, 1982)

The Game: As a cute, fuzzy, harmless little penguin, you roam around an enclosed maze of ice blocks. If this sounds too good to be true – especially for a polar-dwelling avian life form – that’s because you’re not the only critter waddling around in the frozen tundra. Killer Sno-Bees chase little Pengo around the ice, and if they catch up to him and sting him, it’ll cost you a life. But your little flightless waterfowl isn’t completely defenseless. Pengo can push blocks of ice out of the maze, changing the configuration of the playing field and squashing Sno-Bees with a well-timed shove. Clearing the field of Sno-Bees allows you to advance to the next level. (Sega, 1982)

Memories: This is almost a painfully cute game. Cute, fuzzy characters (both good and bad) waddle around the screen, and even if Pengo gets caught by the Sno-Bees, his little dance of defeat is cute. If you win a few levels, a multicolored lineup of penguins do a little Rockettes-style dance for you. But despite the tooth-rotting overabundance of sweetness, Pengo was a very addictive little game.

Pac-Man Plus

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots (10 points) and evading four colorful monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots (50 points) enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period for an escalating score (200, 400, 800 and 1600 points). Periodically, assorted items appear near the center of the maze, and you can consume these for additional points as well. The monsters, once eaten, return to their home base in ghost form and return to chase you anew. If cleared of dots, the maze refills and the game starts again, but just a little bit faster… (Bally/Midway, 1982)

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots (10 points) and evading four colorful monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots (50 points) enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period for an escalating score (200, 400, 800 and 1600 points). Periodically, assorted items appear near the center of the maze, and you can consume these for additional points as well. The monsters, once eaten, return to their home base in ghost form and return to chase you anew. If cleared of dots, the maze refills and the game starts again, but just a little bit faster… (Bally/Midway, 1982)

Memories: Admittedly this wasn’t an especially unique game, but it does have an interesting history.

Ms. Pac-Man

The Game: As the bride of that most famous of single-celled omniphage life forms, your job is pretty simple – eat all the dots, gulp the large blinking dots in each corner of the screen and eat the monsters while they’re blue, and avoid the monsters the rest of the time. Occasionally various fruits and other foods will bounce through the maze, and you can gobble those for extra points. Every so often, just to give you

The Game: As the bride of that most famous of single-celled omniphage life forms, your job is pretty simple – eat all the dots, gulp the large blinking dots in each corner of the screen and eat the monsters while they’re blue, and avoid the monsters the rest of the time. Occasionally various fruits and other foods will bounce through the maze, and you can gobble those for extra points. Every so often, just to give you  a chance to relax, you’ll see a brief intermission chronicling the courtship of Mr. and Mrs. Pac-Man (and a little hint at who the next game would star). (Bally/Midway [under license from Namco], 1982)

a chance to relax, you’ll see a brief intermission chronicling the courtship of Mr. and Mrs. Pac-Man (and a little hint at who the next game would star). (Bally/Midway [under license from Namco], 1982)

Memories: The first real sequel (excluding any altered pirate clones or enhancement kits for the original Pac-Man) in the Pac-Universe, Ms. Pac-Man added quite a few new twists to the original game without changing how it’s played. The new mazes, extra side tunnels (on some mazes), and bouncing fruit were about the only things that could be changed without drastically altering the game (though the later Jr. Pac-Man addition of a scrolling maze was interesting).

Mr. Do!

The Game: As the clownlike elfin dweller of a magic garden, you must avoid or do away with a bunch of nasty critters who are after you, while gobbling up as much yummy fruit as you can. (Taito [under license from Universal], 1982)

The Game: As the clownlike elfin dweller of a magic garden, you must avoid or do away with a bunch of nasty critters who are after you, while gobbling up as much yummy fruit as you can. (Taito [under license from Universal], 1982)

Memories: Mr. Do! is a curious chicken-or-the-egg case. Many elements of Mr. Do! are very similar to Dig Dug. However, Mr. Do! is a much more challenging game.

It was also one of the earliest entries from Universal, a company – unrelated to the Hollywood studio of the same name – whose business model appealed to arcade owners, but became a bugbear for competing arcade game manufacturers. Though Mr. Do! was sold as a standalone cabinet licensed through Taito, Universal’s primary product line was “kit games” – a kit with a new circuit board, marquee and cabinet artwork that could transform any cabinet with similar controls into Universal’s latest offering.

Loco Motion

The Game: A train scoots around a twisty maze of tiles representing overpasses, turns, straightaways and terminals. One portion of the maze is blank, and a train will be lost if it hits that blank tile. Using the joystick, you move the blank tile and one adjacent tile around on the map – even if the train is in transit on that tile – in an effort to keep it moving around the maze, picking up passengers. (Passengers that the train can reach are smiley faces; passengers cut off from the main route are frowning.) If any passengers are cut off for an extended period of time, a monster begins wandering that route, and it’ll cost you a train if it comes in contact with your train. You may have to outrun it with the “speed” button in order to pick up the last passengers and clear the level to move on to a bigger maze. (Centuri (under license from Konami), 1982)

The Game: A train scoots around a twisty maze of tiles representing overpasses, turns, straightaways and terminals. One portion of the maze is blank, and a train will be lost if it hits that blank tile. Using the joystick, you move the blank tile and one adjacent tile around on the map – even if the train is in transit on that tile – in an effort to keep it moving around the maze, picking up passengers. (Passengers that the train can reach are smiley faces; passengers cut off from the main route are frowning.) If any passengers are cut off for an extended period of time, a monster begins wandering that route, and it’ll cost you a train if it comes in contact with your train. You may have to outrun it with the “speed” button in order to pick up the last passengers and clear the level to move on to a bigger maze. (Centuri (under license from Konami), 1982)

Memories: A very minor star in the constellation of early Konami coin-ops (Konami also being responsible for Frogger, Time Pilot and Gyruss), Loco Motion is actually a variation on a very old theme: the 2-D sliding tile puzzle.